Introduction

This research is done by Dr. Vidyadhar Oke, and it is available here on his website. I am just copying all the content here, just so that if their website goes down, this content is still available on the internet. I really like this research and more so this raw style of curiosity and experimentation.

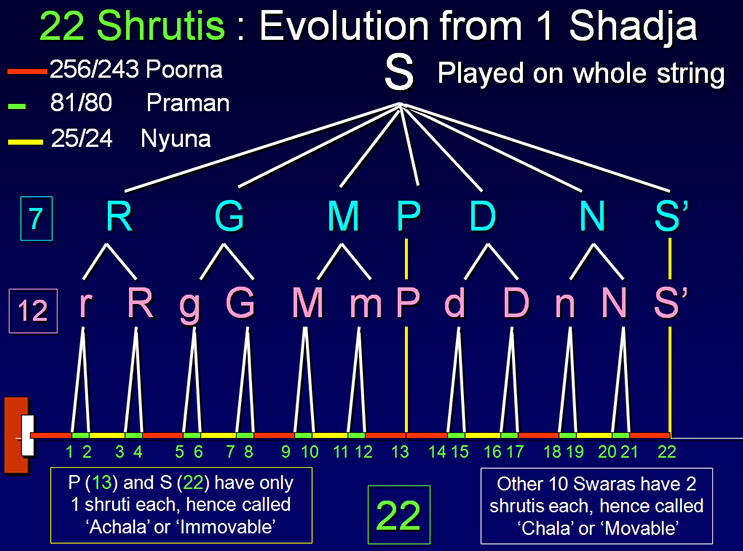

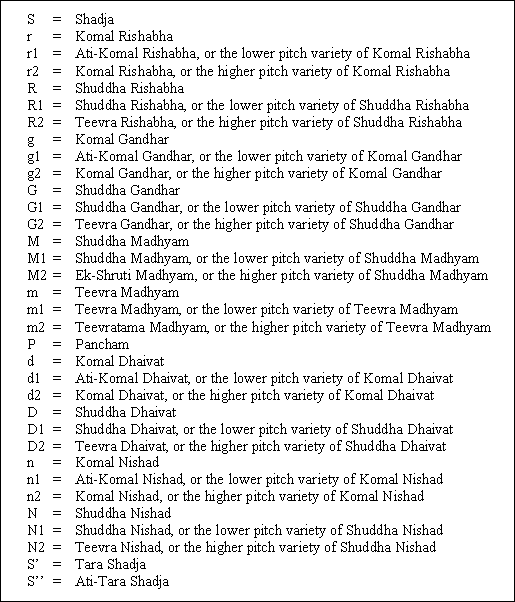

Topic 1 : The short expressions used in this website for 22 Shrutis

The letter alone (like S, m, G, N) denotes the Swara while letter suffixed with a number (like r1, M2, D1) denotes the Shruti of that Swara.

Topic 2 : Non-English Musical, Technical and other terms

| Achala | Immovable notes in the Octave. These do not have a lower and a higher version. They include Shadja, and Pancham. |

| Adhar Swara | An additional note used to support a Swara |

| Ati-Tara | Extremely high pitched. |

| Besur | Non-melodious. Out of tune. |

| Bharatmuni | An ancient Indian Scholar, the author of Natya-Shastra, a treatise on Music and Dance. |

| Bharat Ratna | The highest honour in India conferred by Government of India. |

| Bhava | Relationship or Ratio. |

| Bhedasthana | The alternative version of the note. |

| Chadha/i | Note of a higher frequency |

| Chakra | Wheel |

| Dha | Short form of Dhaivat. Equivalent of ‘La’ in Western Classical music. There are 2 notes of Dhaivat in the Octave. One, Komal Dhaivat, and the other, Shuddha Dhaivat. |

| Dhaivat | Equivalent of ‘La’ in Western Classical music. |

| Dvavinshak | The Indian Saptak (Scale) consisting of 22 Shrutis |

| Eka | One |

| Eka-Shruti | At a distance of one Shruti. |

| Ga | Short form of Gandhar. Equivalent of ‘Mi’ in Western Classical music. There are 2 notes of Gandhar in the Octave. One, Komal Gandhar, and the other, Shuddha Gandhar. |

| Gandhar | Equivalent of ‘Mi’ in Western Classical music. |

| Guru | Teacher |

| Hindustani | Indian. Usually used to denote ‘North’ Indian music. |

| Jod Swaras | Additional notes used to link 2 Swaras |

| Kana Sparsha | A note used slightly or taken quickly in transit |

| Karnatak | Denotes ‘South’ Indian music. |

| Kharja | Low pitched, Bass, also called as ‘Mandra’. |

| Komal | Signifies lower (flat) version of the note. |

| Komal Dha | 9th note in the Octave. |

| Komal Ga | 4th note in the Octave. |

| Komal Ni | 11th note in the Octave. |

| Komal Re | 2nd note in the Octave. |

| Kramasthana | The sequential version of the note. |

| Ma | Short form of Madhyam. Equivalent of ‘Fa’ in Western Classical music. There are 2 notes of Madhyam in the Octave. One, Shuddha Madhyam, and the other, Teevra Madhyam. |

| Madhya | Medium (normal) pitched. |

| Madhyam | Equivalent of ‘Fa’ in Western Classical music. |

| Mandra | Low pitched, Bass, also called as ‘Kharja’. |

| Nadaguna | When the source object of sound vibrates to produce different harmonics, their mixture is interpreted by the human ear as having a ‘particular’ quality. This Harmonic profile of the source is termed as “Timbre” or “Nadaguna”, and is very characteristic of the source. |

| Nirman | Creation |

| Natya-Shastra | a treatise on Music and Dance written by Bharatmuni, an ancient Indian scholar |

| Ni | Short form of Nishad. Equivalent of ‘Ti’ in Western Classical music. There are 2 notes of Nishad in the Octave. One, Komal Nishad, and the other, Shuddha Nishad. |

| Nyasa | Holding of note in a steady manner. |

| Nyuna Shruti | Ratio of 1.041666666 (25/24) existing between the 3rd and the 4th Shruti and repeating later at regular intervals. |

| Padmashree | An honour conferred by the Govt. of India on exemplary contribution. |

| Pancham | Equivalent of ‘So’ in Western classical music. 8th note in the Octave. |

| Pancha-maha-bhootas | The big and essential 5 elements of the world, namely, the fire, water, earth, air and space. |

| Parampara | Tradition. |

| Poornna Shruti | Ratio of 1.053497942 (256/243) existing between the 1st and the 2nd Shruti and repeating later at regular intervals. |

| Poorvanga | The proximal (S:P) portion of Raga/Octave. |

| Prakrut | Natural. |

| Pramana Shruti | Ratio of 1.0125 (81/80) existing between the 2nd Shruti and 3rd Shruti and repeating later at regular intervals. |

| Raga | The perceptible creation of a ‘musical design’ made by using selected notes in the Octave, by traditional methods of rendering these notes. |

| Raga sangeet | Music created by Raga. |

| Re | Short form of Rishabha. Equivalent of ‘Re’ in Western Classical music.There are 2 notes of Rishabha in the Octave. One, Komal Rishabha, and the other, Shuddha Rishabha. |

| Sa | Short form of Shadja. Fundamental or the 1st note in the Octave. Equivalent of ‘Do’ in Western Classical music. |

| Samvad | Musical relationship. |

| Samsad | A musical body. |

| Saptak | Octave. |

| Shadja | The fundamental tone or 1st note in the Octave. |

| Shishya | Student. |

| Shruti | Musical note. There are 22 basic musical notes within an Octave as per Indian Classical Music. |

| Shrutyantara | Distance between different musical notes. |

| Shuddha | Seven basic notes in the Saptak, namely, S, R, G, M, P, D, N. Also called as ‘Prakrut’ (Natural notes). |

| Shuddha Dha | 10th note in the Octave. |

| Shuddha Ga | 5th note in the Octave. |

| Shuddha Ma | 6th note in the Octave. |

| Shuddha Ni | 12th note in the Octave. |

| Shuddha Re | 3rd note in the Octave. |

| Surel | Melodious. In tune. |

| Swara | A musical note selected from 22 basic musical notes or Shrutis for performance (in a raga). |

| Susamvad | Consonance. |

| Swarakshetra | A ‘range’ of individual frequencies, which are all identified as the ‘same’ musical note for 10 notes in a Saptkak (excluding Shadja and Pancham) |

| Swayambhu | Naturally created. |

| Tanpura | A tradionally used musical instrument (of well-tuned strings) in India creating a backdrop of harmonic musical sounds on which a classical performance is made. |

| Tara | High pitched. |

| Teevra | Signifies a higher (sharp) version of the note. |

| Teevra Ma | 7th note in the Octave. |

| Teevratama | Signifies a still higher version of note than the Teevra version. |

| Utara/i | Note of a lower frequency |

| Uttaranga | The distal (P:S’) portion of a Raga/Octave. |

| Vikrut | Five notes in the Octave excluding, Shuddha notes. They signify flat or sharp versions. They are r, g, m, d, n. |

Topic 3 : Introduction to the Harmonium

The Harmonium was first patented by Alexandre Francois DeBain in France on 9th August 1840.

It was imported in India by British Officers ruling India, this was around the 1860s and since then, the Harmonium has remained as one of the most popular musical instruments in India.

Today, it is being played actively not only in Classical music but also in Folk music, Dramas, and Cinema music. The position of Harmonium has however remained controversial in Indian Classical Music, so much so that it was even banned by All India Radio from 1940-1971.

This was allegedly due to the ‘European’ tuning of the instrument which did not provide any of the ‘Indian’ 22 Shrutis.

However, having been played for over 150 years, the Harmonium has become a part of most Indian homes that follow and cherish our rich culture.

I started playing the harmonium ever since I remember as both, my mother and her father were harmonium players.

Later, I was very fortunate to learn harmonium solo/accompaniment for about 25 years from my Guru, Late Pt. Govindrao Patawardhan.

During my music career, I observed that the harmonium did not have a universal acceptance from Indian Classical Vocalists due to what was called as the ‘tempered tuning’.

Conversely, string instruments such as the Sarangi or the Violin were considered more acceptable for accompaniment by vocalists. When I made enquiries about the details of the so called ‘tempered’ tuning and it’s differences from ‘Indian Classical’ tuning, to my surprise, I found very little information, and that too, inconsistent.

At that point, I decided to plunge into this 22 Shruti research in 2004, after I had just retired from my pharmaceutical career.

Fortunately, after 2 decades of beginning this work, the research work and its applications are now getting a lot of awareness in many parts of the world.

Topic 4 : Production of Natural Sounds : Harmonic, Partials, Timbre

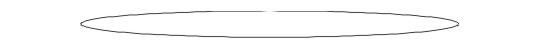

The most natural example of sound production in the nature is of a vibrating single string. We all know that a string tightly stretched across 2 ends produces a sound on plucking.

“1st Harmonic” or “Shadja” or”Fundamental Tone”

When a string is made to vibrate by plucking, to start with it vibrates in it’s full length; and the makes a certain sound. This is called as “Shadja” or the “Fundamental Tone”,or “1st Harmonic” . For the purpose of understanding, we shall take it’s frequency as 100 hz.

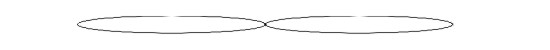

“2nd Harmonic” or “Tara Shadja”

Immediately thereafter, as the energy put in the string for plucking reduces, the string starts vibrating in 2 parts. This produces a sound of 200 hz called as the 2nd Harmonic. This is “Tara Shadja” as we know.

“3rd Harmonic” or “Pancham”

Immediately thereafter, as the energy put in the string for plucking reduces further, the string starts vibrating in 3 parts. This produces a sound of 300 hz called as 3rd Harmonic. This is however perceived by our brain as of 150 hz (our brain has the spectrum of perception of 100 hz to 200 hz) or “Pancham” (5th) as we know.

“4th Harmonic” or “Ati-Tara Shadja”

Immediately thereafter, as the energy put in the string for plucking reduces further, the string starts vibrating in 4 parts. This produces a sound of 400 hz called as 4th Harmonic. This is perceived by our brain as of 200 hz (our brain has the spectrum of perception of 100 hz to 200 hz) or Tara Shadja again.

“5th Harmonic” or “Gandhar”

Immediately thereafter, as the energy put in the string for plucking reduces further, the string starts vibrating in 5 parts. This produces a sound of 500 hz called as 5th Harmonic. This is perceived by our brain as equivalent of 250 hz or 125 hz or Gandhar.

After this stage, the energy put in the string for plucking reduces so much that further harmonics (6th, 7th, 8th and so on) are barely heard.

Harmonics :

The Sounds created which are in multiple proportions to the frequency of the Fundamental or Shadja (100,200,300,400,500 as above), are called as “Harmonics”, because they are in “harmony” with the Shadja. They sound very pleasant to the human ear. We all have experienced that Pancham (3rd harmonic) and Gandhar (5th harmonic) are most pleasant. Tanpura creates an atmosphere of dominant Shadja-Gandha-Pancham.

Partials :

When a sound source produces ‘other than harmonic’ frequencies, they are termed as “inharmonics” or “partials”. These are not in harmony with Shadja and are unpleasant to the human ear.

Timbre (Harmonic Profile) :

When the source object of sound (string in this case) vibrates again and again, different harmonics/partials generated mix, and this mixture is interpreted by human ear as having a ‘particular’ quality. This Harmonic profile of the source is termed as “Timbre” or “Nadaguna”.

The Timbre of every sound source is ‘typical and different’ from each other. That is how we recognize sounds of different instruments and even sounds of people, by their ‘typical and different’ Timbres.

The Harmonics coming out of string instruments which have long strings like the Violin and Sarangi have a Harmonic profile similar to that of human voice and hence are considered as best for accompaniment to human singing.

Topic 5 : The difference between “Nada”, “Shruti” and “Swara”

Unfortunately, the word ‘Swara’ carrIES 2 different meanings!

- Swaras (in a ‘Saptak’) : These are 12 different (7 Shuddha and 5 Vikrut) types of musical notes identifiable by a musical ear in a Saptak (Octave). The 10 of these (excluding the Shadja and Panchama) actually have a ‘Range’ or a ‘Group’ of individual frequencies, which are all identified as the ‘same’ Swara ! This range therefore should have been called as ‘Swarakshetra’, (meaning frequency range for a Musical Note) and not Swaras.

- Swaras (in a Raga) : These are precise single frequencies within a Swarakshetra which make Aroha and Avaroha of a Raga. These should be called as (real) ‘Swaras’.

Thus, ‘Swara’ and ‘Swarakshetra’ are different. ‘Swara’ is a chosen (single) frequency within a ‘Swarakshetra’ (frequency range).

Now, what is the difference between Nada, Shruti, and Swara ?

There are innumerable musical sounds as individual frequencies or “Nadas” within 2 Shadjas (i.e.,in an Octave or Saptak). In order to create Raga-sangeet, we must be able to “stay” (do Nyasa) on some of them. These selected “Nadas” to be used for “stay (Nyasa)” are called as “Shrutis” and they are 22. (Why are they 22 is explained in Topics 22 and 23). Out of these 22 Shrutis, the ones selected for a particular Raga become themselves, the “Swaras” of that Raga.

Thus,

- All individual frequencies between 2 Shadjas are “Nadas”

- Those Nadas selected for becoming steady (Nyasa) in Ragas are “Shrutis”

- Those Shrutis selected in a Raga are “Swaras”

Raga therefore consists of ‘Swaras’ connected by ‘Nadas’ !

The difference between ‘Shruti’ and ‘Swara’ is clearly described in ancient music literature.

The word ‘Shruti’ comes from the ancient Sanskrit saying “Shruyate iti shruti”. This means that when a Nada is heard so clearly that it can be ‘identified’ it is called as a ‘Shruti’.

This is possible only if we ‘stay’ on a Nada (Nyasa) which allows the human ear to recognize it as a specific ‘musical’ note. In contrast, the Nadas which lie ‘in-between Shrutis’ are always used to connect Swaras (as in Aalap or Meend). We do ‘not’ become steady on them, they are individually unidentifiable due to their rendering as a quick movement and called as “Nadas”, they are not to be called as “Shrutis”.

Pt. Ahobal mentions in Sangeet-Parijat:

“Ahi-kundalavat tatra bhedokti shastra sammatah”, meaning, ‘Shruti’ is like a ‘Quiet (coiled) snake’ (unused). When the same becomes ‘active’ (when used in a Raga) it becomes like a ‘Moving snake’ and is called as ‘Swara’. (eg., Raga Bhoop has S, R1, G1, P and D1 as 5 Swaras, and that leaves behind the unused 17 other Shrutis (out of a total of 22).

Further, Pt. Vishwabasu opines that those notes performed by a ‘Kana-Sparsha’ (or by slight touch) in a Raga, should be called as ‘Shruti’ and others used boldly (with a Nyasa or by hold) should be called as ‘Swaras’. He thus calls all frequencies or ‘Nadas as Shrutis’, and those selected in a Raga for stay or Nyasa as ‘Swaras’.

Since such a clear difference in these terms has not been practiced or used seriously by both students and pandits of Classical music, unnecessary confusion has been created.

Hence, we should simply say that:

- The Innumerable frequencies between 2 Shadjas are “Nadas”

- Selected Nadas for ‘stay’ or ‘nyasa’ are “Shrutis”, (and they are 22) and

- Selected Shrutis in a particular Raga are “Swaras”

Unfortunately, many music students and teachers too, call these additional ‘connecting’ Nadas also as Shrutis, and therefore carry the wrong understanding that Shrutis are innumerable !

In other words, and very simply, the “Nadas” are all Cricket players, “Shrutis” are those 22 selected in a team, and “Swaras” are those selected for a particular match!

Topic 6 : Previous Research work on 22 Shrutis

Many researchers have tried to discover the Mathematics behind 22 shrutis.

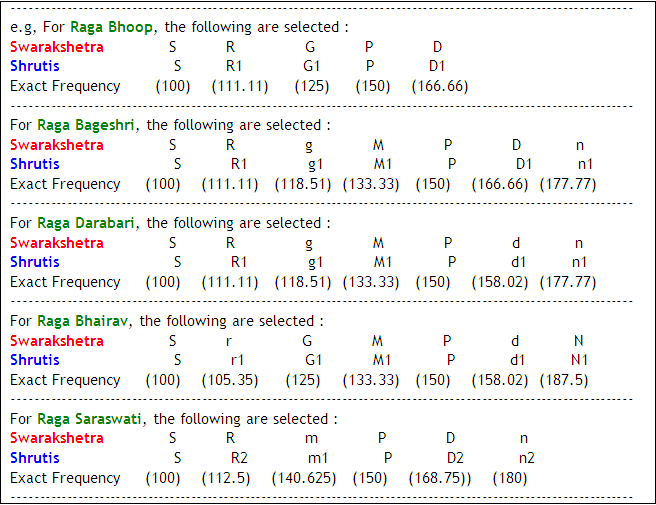

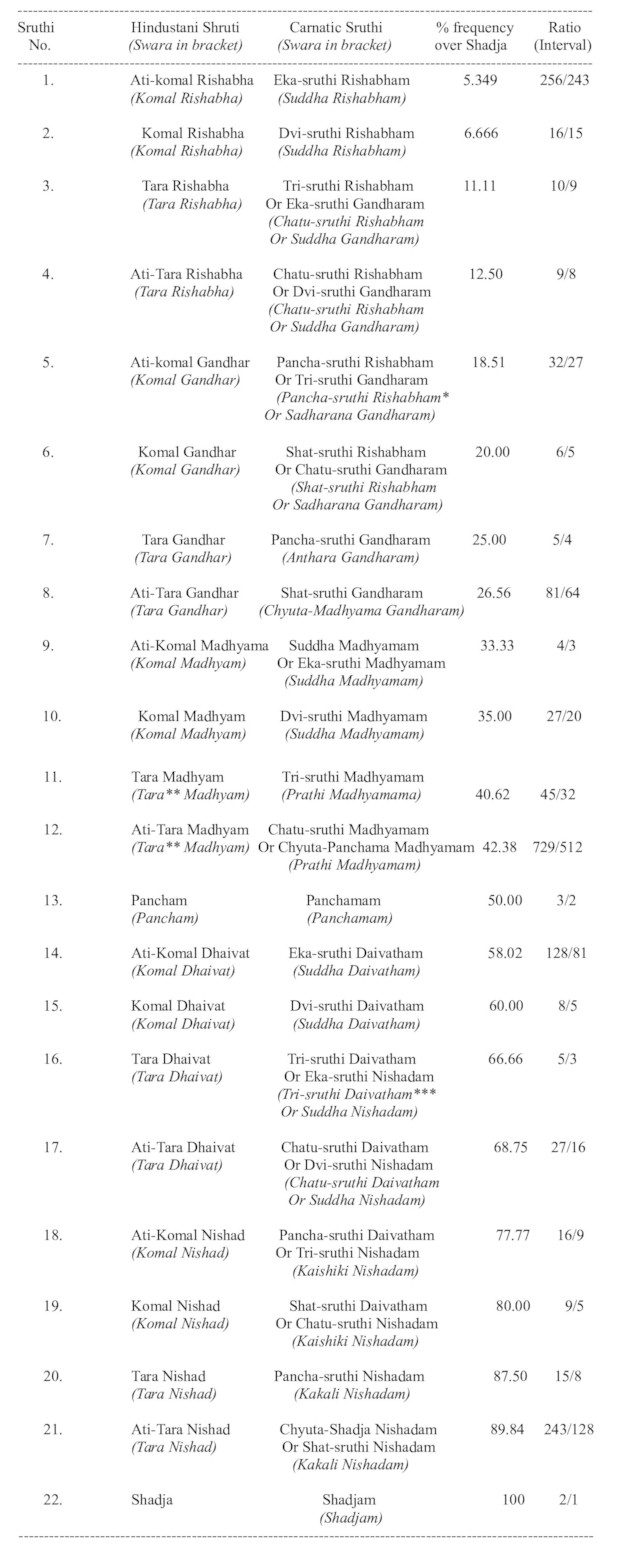

One scholar from Dombivli named Mr. Ranade has written a book ‘Shruti-Rahasya’ and given the Shruti-values as obtained by his research and he has also quoted the work of other prominent people including Pundits like Achrekar, Mulay, Clemants, Onkarnath, Brihaspati (refer to following table).

The table below shows % distances from Shadja of all the notes, as cited by different research workers. (Adopted by converting Hz values to % from Shadja, from table given in Ref : Shruti-Rahasya by G.G.Ranade, 1979, p13, 14).

There are also other values (including some on the Internet) regarding the frequencies of 22 Shrutis. Unfortunately, these researchers in music have given different values of the same Shrutis and therefore in the end, the reader is left in considerable confusion.

In the absense of the elaboration of the underlying accurate mathematical principle, it was not surprising that the end points were different.

Topic 7 : The Story Of The World’s First Shruti-Harmonium

The world’s first Harmonium was made over 100 years ago (in 1911) by Mr. Earnest Clements, a Civil Servant at Ahmedabad and a music enthusiast, and Mr. Krishnaji Ballal Deval, a retired deputy collector from Sangli.

The task was difficult and achieved with a unique methodology.

They first wanted to precisely understand the frequencies used by stalwarts of Indian Classical Music. So first they created a string instrument, like a Veena, with just 2 strings. They would approach a stalwart, and then tune both strings in the Shadja.

Later, the stalwart was made to sing a raga and asked to stay on every swara. As he stayed, Mr. Deval would play the same note on one of the strings, get a consent from the stalwart that it exactly is the same note being sung, and then calculate the % distance of the string from one end to arrive at the frequency using Galilio’s Law.

There could not have been a more ingenious and accurate method at that time to arrive at shruti positions.

They engaged several top class singers including Ustad Abdul Karim Khansaheb and derived the shruti positions very accurately.

Further, using good offices of Mr. Clements and making use of these shrutis, the world’s 1st Shruti-Harmonium called as Indian (Hindu) harmonium was made in London by Mr. H. K. Moore of M/S Moore and Moore company at the New Oxford Street, London.

It was patented in London (Specifications of Inventions etc 1911, 1xxxviii, London Patent Office,1913,under no.15548). The details of this harmonium are fully described in a book written by Mr. Clements : Introduction to the study of Indian Music, Longmans, Green and Co., 1913, priced at $ 2 net).

Also, Mr. Deval had earlier written 2 books :

- The Hindu Musical Scale and Twenty Two Shrutees (1910), and

- Music East and West Compared (1908).

Every Octave had 23 notes, and 11 extra notes were played by pressure upon studs which pierced the black and white manuals. The cost of the Harmonium was 20 Pounds.

Finally the new instrument was decided to be unveiled in the 1916 All India Music Conference (AIMC) in Baroda convened by Mr. Bhatkhande, who already had reservations about Mr. Deval not being a musician himself and still claiming to document the science behind ancient shrutis.

Mr. Deval and Mr. Clements presented their ‘Shruti-Harmonium’ to the audience.

Next day, a group of Mr. Bhatkhande’s supporters were recruited to oppose the instrument vehemently and conclude that the notes it gave were not those used in Indian Ragas. To add fuel to the fire, Mr. Clements gave a presentation later on how the modified European staff notation could capture all the nuances of the Indian Classical Music better than the earlier notation systems.

This too received a negative response largely due to the underlying fear that the Britishers were now gearing up to swallow the Indian Classical Music as well!

The ‘shruti-harmonium’ was opposed ignoring the fact that the notes coming out of the instrument were those actually sung by no other than the Maestro of Kirana Gharana Ustad Abdul Karim Khan in the first place !

It must be noted that Mr. Bhatkhande was not very appreciative of Abdul Karim Khan.

The worse was that the same dramatic battle between Mr. Deval and Mr. Clements on one side and Mr. Bhatkhande’s supporters on the other also repeated in the next AIMC at Lucknow in 1918 !

There once again the ‘shruti-harmonium’ was presented to deaf ears, several prejudiced questions were raised about Mr. Deval and he not being a performer could not satisfy the prejudiced audience.

He had to say that he was not there to appear for an examination. On that, Mr. Ramaswamy Iyer, the Chairman advised sarcastically that if Mr. Deval cannot answer the questions, he should retire from his lecture just as he had retired from his deputy collectorship!

Thus it was a political defeat for the world’s 1st Shruti-Harmonium and the instrument became obsolete in just about 4-5 years after these events.

Today we know that in this harmonium made 100 years ago, 17/22 shrutis were perfect, and other 5 were only marginally different.

What a tragedy!

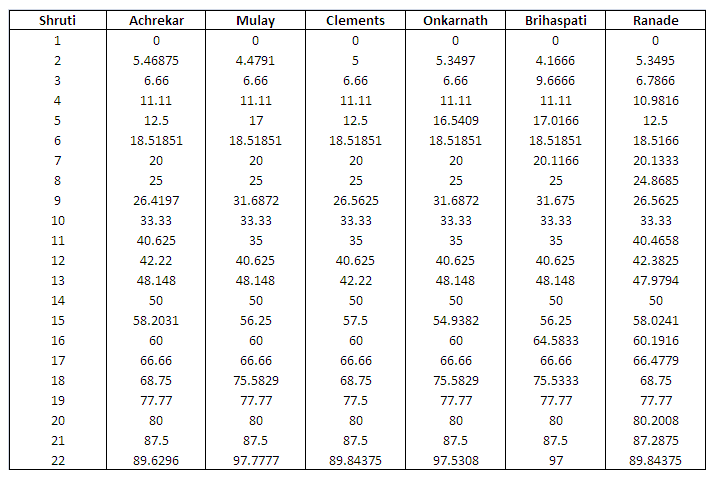

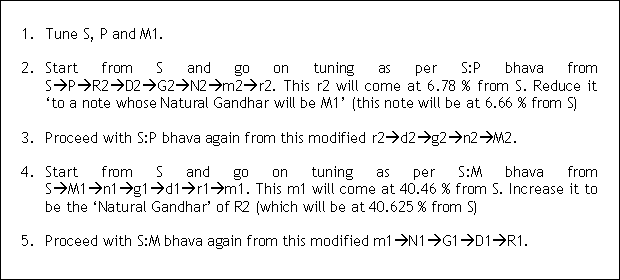

Topic 8 : The Logic behind 22 Shrutis (‘Shruti-Nirman Chakra’)

The ancient logic on how different musical notes are created in a Saptak is very insightful and relevant.

The fundamental notes in music are S and P and the Tanpura is tuned to these notes for the same reason.

Other than P, the next important note is M because, the upper S’ becomes the P of it.

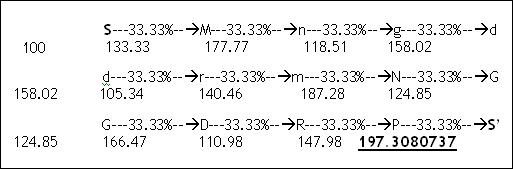

The natural ratio of the frequencies of S:P is 100:150, and of S:M is 100:133.33333. These are obtainable after an analysis of an extremely well-tuned Tanpura. In other words, from any musical note (taken as 100), the note at 133.33333 % is it’s Madhyam, and the note at 150 % is it’s Pancham.

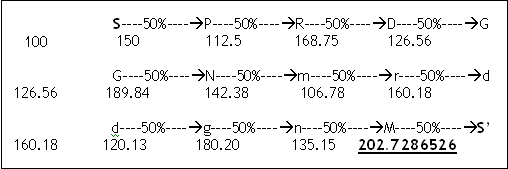

Therefore, beginning from any Shadja, if we continue the S:P cycle ahead by adding 50 % to the frequency of the earlier note, we shall complete the cycle, coming back to S’ and giving 12 positions or places.

Similarly, if we continue the S:M cycle ahead by adding 33.33333 % to the earlier note, we shall complete the cycle, coming back to S’ giving 12 additional positions or places.

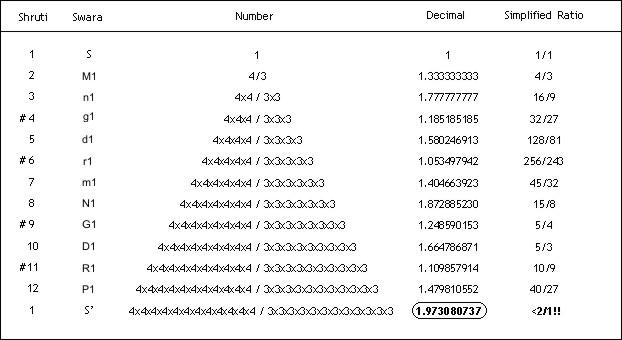

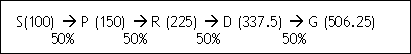

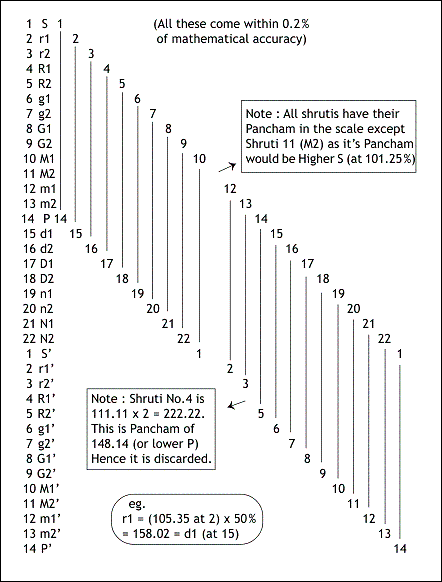

In total, 24 places or 24 musical notes are obtained. (Refer to following figure)

Figure shows ‘Shruti-Nirman Chakra’ .

The clockwise cycle is Shadja:Pancham (S:P) and the anticlockwise cycle is Shadja:Madhyam (S:M).

Thus, we get 24 places or musical notes or shrutis at the natural ratios of S:P and S:M.

Out of these, S and P have been considered ‘Achala’ or immovable or fixed by our ancestors. Subtracting these 2 from 24, we get 22 Shrutis.

The exact frequencies of these 24 positions were however obscure for all these years because of the unresolved mathematical difficulties explained in Topic 13.

Topic 9 : The Meaning And Criticism Of The ‘Tempered’ Scale

The word ‘Temperament’ indicates ‘building up of musical notes’.

There can be many ways of such build-ups from Shadja to Tara Shadja. Hence, there are Equitempered scales with 12, 19, 22, 24, 31, 53, and 72 notes.

When we use the word ‘tempered’ in the context of Harmonium, it means a short form of ‘12-Tone-Equi-Tempered (ET) scale’ popular in the world for the last 200 years and which is tuned in Pianos, Organs, Accordions and all traditional Harmoniums.

The 12-Tone ET scale permits an ‘equal’ amount of ‘mis-tuning’ in each note, without having to provide 12 pitches per Octave, enabling a player to play from any key taken as the fundamental tone or Shadja.

The difference in pitches thus distributed equally is called as ‘dividing roughness equally in 12 notes’, and is termed as ‘Wolf’. Wolf has to be set right, otherwise the instrument will howl out of tune.

This scale is therefore criticized even in the West by eminent musicians as it does not have ‘natural’ notes, and to that extent it is ‘tampered’.

For eg.,

Yehudi Menuhin mentions in his autobiography entitled ‘An unfinished Journey’ that:

“(The) West had to invent the tempered scale, each note adjusted up or down from it’s true center, to reconcile to different keys. I can’t pretend to regret a development that has fed my whole musical life, but equally, it is difficult to deny that tempered scale corrupts our western ears…”

~ YEHUDI MENUHIN

Brian Godden from Santa Rosea, USA, another Western scholar and a student of Ustad Ali Akbar Khan Saheb, mentions on his website that:

“For the past 200 years, the ears, minds and hearts of Westerners have been saturated with ET scale consisting of 12 equally spaced ‘Out-of-tune’ notes based on a ratio of 1.0594631. They hear ET as ‘in tune’…”

Bob Fink, yet another Western scholar mentions on his website that:

“Most ears are forgiving. Millions of people have adopted to the tempered ‘dissonance’ of piano tunings. They hear it with ‘Self-delusional’ mental adjustments…”

Topic 10 : Positions of notes in Equitempered (ET) Scale

Not many are aware that the mathematical theory of the ET scale was first published by Chu Tsai-Yu in China during the days of the Ming Dynasty in 1584.

In those days, there used to be a lot of trade between Europe and China. In 1636, i.e, barely 52 years later, Simon Stevin and Marin Mersenne wrote about ET scale in Europe.

The Ming Dynasty ended in 1592, however, Chu’s publication was to change the world’s music forever. ET scale was used first in Germany in 1690 and the Organ in Newcastle-upon-Tyne at the St.Nicholas Church was the first to be tuned to ET scale in 1842.

Each note in the ET scale is at a distance of a multiple of 1.0594631 from the previous note.

The tuning of the keyboards of Pianos, Organs, Accordions, and Harmoniums is done in this manner.

This magic number is the “12th root of 2”.

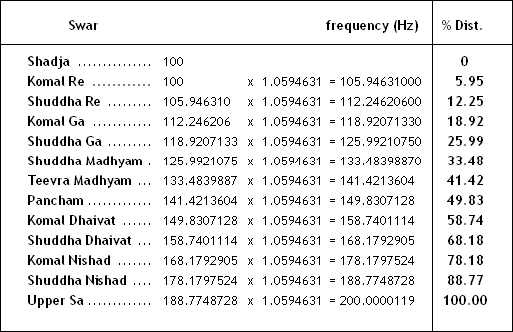

This means that when any number is multiplied by this magic number 12 times, the original number will be doubled. (Refer to following table)

Table shows % distances of every note in Octave (Saptak) as per 12-Tone-Equitempered (ET) Scale (as tuned in Pianos, Synthesizers, Keyboards, Organs, Harmoniums, Accordions)

Remember : Multiply Hz frequency of any key by 1.0594631 to get the frequency of next key;

and divide to get the frequency of the previous key.

From S

Take any starting key as S = say 100 Hz

Note : All the 12 notes in the Equitempered Scale are “Unnatural”.

Practical Example : Komal Dhaivat of ‘A’ or Saphet 6 is ‘F’. ‘A’ is 440 Hz. F will be at a distance of Komal Dhaivat i.e., at 58.74%. 440 x 58.74% + = 698.456 Hz.

In ET scale, if we listen to the Shadja and Gandhar (played together) in any key taken as the Shadja, we find that there is no consonance.

This is because, the S-G distance in the tempered scale is almost 26% whereas the Natural S-G distance as heard on a Tanpura is a pure 25%. S-P distance in tempered scale is 49.83% whereas the Natural S-P distance as heard on a Tanpura is a pure 50%.

Similarly, there are differences in all other notes between the ET scale and the Natural scale.

Topic 11 : Capacity of the human ear to differentiate Sound frequencies.

The ability of the ear to perceive a change in Swara varies from person to person, from an untrained to a trained ear, from noisy to quiet places, from whether 1 Swara is played or many Swaras are played at a time and so on.

It can actually be different even in the same person at different times or on different days.

It can be measured by the ‘Musical Quotient’ (Swaranka) as per the research work of Dr. Govind Ketkar of Dombivli (Dist. Thane, Maharashtra, India).

He has found that if a Swara changes by 2.5 %, a normal person can perceive the difference. And, a musician can find the difference even if the Swara changes by only 1.5 %.

He has also shown that by practicing certain Yoga-like techniques, this ability can be improved.

This ability is not measured in Hz because, at the lower end of a keyboard, 1 % of ‘A’ (110 Hz) is 1.1 Hz; whereas in the higher Saptak (Octave) of a keyboard, 1 % of the same note ‘A’ (880 Hz) is 8.8 Hz ! Therefore, the unit of this measurement is not ‘Hz’, but ’% change from Hz of Shadja’.

Further, my own observation is that, if the 2 notes are played ‘together’ (at the same time), an average trained ear of a performing musician (like myself) can measure as minute a difference as 0.0594631 % !

This difference is nothing but ‘1 Cent’ between any 2 consecutive keys on a keyboard or = 1 % of the difference in Hz between the two consecutive keys on a keyboard. (For eg., if we start from key A (220 Hz) of the keyboard, the next key B flat will be at 220 x 1.0594631 = 233.081882. The difference between these 2 keys is 233.081882 minus 220 = 13.081882 (or 100 cents). Therefore, 1 cent will be = 0.13081882. This is 0.0594631 % of 220.)

Such an extreme ability of a trained listener allows us to tune a Tanpura or any other instrument perfectly well with any Shadja on Harmonium, as we normally do before a concert.

Remember however, that ‘1 Cent’ varies in ‘Hz’ from lower to higher Saptak on a keyboard.

Topic 12 : Indian Natural Scale

The ‘natural’ scale is the scale which produces natural sounds which are naturally consonant with the Shadja and are pleasing to the ear.

When we hear an extremely well-tuned Tanpura, we find that it makes 3 such fundamental sounds.

Firstly, the ‘Shadja’ in which it is tuned, it’s ‘Pancham’, and the natural ‘Gandhar’. These 3 notes when taken serially and their frequencies analysed, Shadja, Gandhar, and Pancham are found to be situated at a fixed distance.

If Shadja is of 100 Hz, Gandhar is at 125 Hz, and Pancham at 150 Hz. How these natural harmonics/frequencies evolve has already been shown in Topic 4.

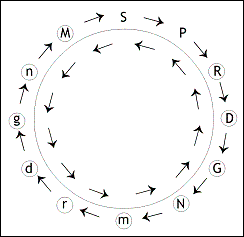

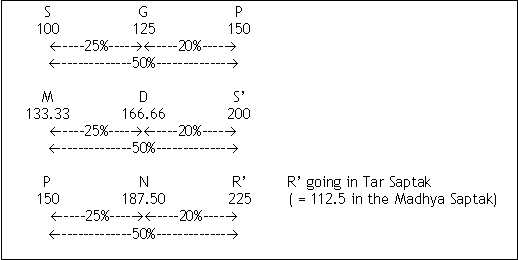

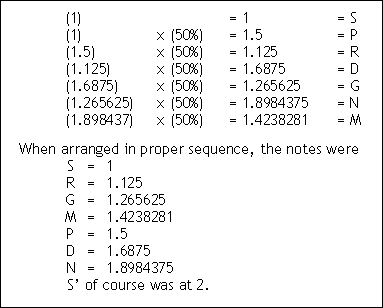

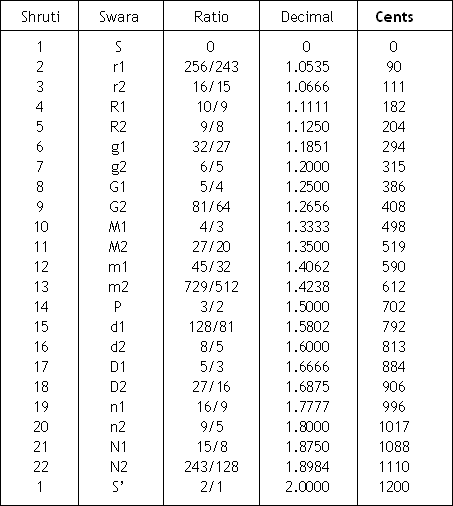

S:G:P are therefore the basic 3 universally accepted natural musical notes and they give rise to the 7 natural notes as shown below. (Refer to following table)

Table shows the 7 Natural notes with their Natural positions

This system gives us 3 perfectly consonant triads at a ratio of 100:125:150 consisting of S-G-P, M-D-S’, and P-N-R’.

Topic 13 : Mathematical difficulties in calculating 22 Shrutis.

Extending the logic of Shruti-Nirman-Chakras (Topic 8) ,it may appear that if we complete the cycles S:P and S:M respectively by adding 50 % and 33.333333 % to the frequencies of the earlier notes, we can get the frequency values of 24 Shrutis.

To our horror, if we complete such cycles, we will have a problem in the end.

Because, if the starting point is taken as 100, S:P cycle which should end at 200, actually ends at 202.7286526 ! This constitutes the famous ‘Pythagorean Error’.

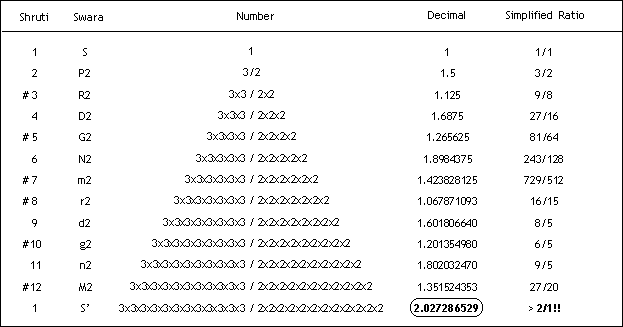

No one knows why this happens but this is termed as ‘Pythagorean Comma’ (Comma means Error in Greek), meaning, not an error made by Pythagoras, but an error or natural flaw in musical numbers as found by Pythagoras. (Refer to following table)

The accompanying table shows Pythagorean Comma (Error) : Sa-Pa Cycle

Remember : Multiply every note by 3/2 = 1.5 to get the frequency of the next note (Pancham of previous note).

_(# Under the decimal column, when the value goes beyond 2 in the next Saptak,

it is brought back to the original Saptak by dividing the value by 2, or it’s multiples)

Very interestingly, it can be seen that the upper S’ which should be 2, comes actually somewhat more as 2.027286529. This difference is known as ‘Pythagorean Comma’, the mathematical value of which is 2.027286529 divided by 2.0 = 1.013643264. This cycle is therefore ‘Chadhi’ or giving us ‘higher frequency notes’.

All the Swaras are therefore suffixed by 2 indicating a ‘higher’ Shruti.

Therefore, if we start from a Shadja with say frequency of 100 Hz, the upper Shadja will come at 202.7286529, and not at 200. (Refer to following table.)

Table shows that S:P cycle goes beyond S’ (Pythagorean Comma) (Take exact values from above table)

Even the Sa:Ma cycle ends at 197.3080737 and not 200. (Refer to following table)

Accompanying Table shows Pythagorean Comma (Error) : Sa-Ma Cycle

Remember : Multiply every note by 4/3 = 1.333333333 to get the frequency of the next note (Madhyam of previous note)

_(# Under the decimal column, when the value goes beyond 2 in the next Saptak,

it is brought back to the original Saptak by dividing the value by 2, or it’s multiples.)

This cycle is therefore ‘Utari’ or giving us ‘lower frequency notes’. All the Swaras are therefore suffixed by 1 indicating a ‘lower’ Shruti.

Therefore, if we start from a Shadja with say frequency of 100 Hz, the upper Shadja will come at 197.3080737, and not at 200. (Refer to following table)

Table shows S:M cycle falls short of S’ (Take exact values from above tables)

This means that the Shrutis thus obtained are not accurate as S:P cycle ‘overshoots’ and S:M cycle ‘falls short’!

I realized at this point that there must be another way or principle to reach 22 shrutis accurately!

Topic 14 : Pythagoraen Octave (Scale)

We will need to understand few other mathematically relevant points before we are able to understand the detail mathematics of 22 Shrutis. Pythagoras had worked out his own scale of notes called as ‘Pythagorean Octave’.

As he was a Mathematician, his method of finding the positions of notes was simply a cycle of Panchams which are called ‘Pure fifths’ in the West.

When Shadja has a frequency of 100 Hz, Pancham can be found only and accurately on 150 Hz. Progressively, he found further notes at 50 % addition of previous notes till he completed his octave.

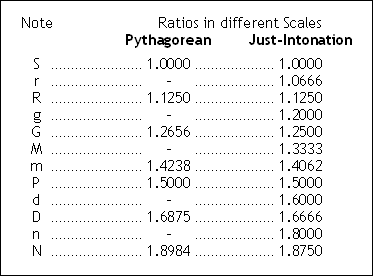

As, such a Pancham is also accurately judged by the brain, this is not only a mathematically elegant system, but also one of the easiest to tune by ear. (Refer to following table)

Table shows the mathematical creation of Pythagorean Octave

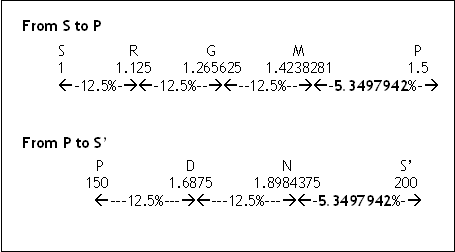

Topic 15 : Importance of the Pythagorean Scale : ‘Pythagorean Limma’

Pythagorean Scale is important because, an extremely important number called “Pythagorean Limma” is hidden in this scale. Pythagoras analyzed the % distances between the above consecutive notes and found them as under. (Refer to following table)

Table shows % distances between notes in Pythagorean scale

Thus, Pythagoras found that the distances between S-R, R-G, G-M, P-D, and D-N as 12.5%, and that between M-P and N-S’ as 5.3497942 %.

He considered this distance as ‘Limma’ meaning ‘left over’ in Greek. This means that when we go on adding 12.5% from S, the ‘left over’ distance ending in P is the same as that ending in S’. This is the ‘Pythagorean Limma’.

It’s value is 1.053497942, rounded off to 1.0535, because; as shown above, 1.4238281 x 1.0535 = 1.5; and 1.8984375 x 1.0535 = 2.

This measurement of 1.053497942 (or 1.0535) appears in the fundamental construction of 22 Shrutis.

Pythagoras was a great Mathematician, Musicologist, and an Astronomer. To him, number was everything. He considered 4 sets of numbers. For him…

- ‘Only numbers’ constituted ⇒ Mathematics

- ‘Numbers and space’ constituted ⇒ Geometry

- ‘Numbers and time’ constituted ⇒ Music

- ‘Numbers with space and time’, all together, constituted ⇒ Astronomy

He saw a great unity in all creations in nature, and felt that music was a ‘Melody of Spheres (Planets)‘. He trusted that musical notes and the orbital distances between planets would have a relation.

Thus, his musical octave gave us the extremely important ‘Pythagorean Limma’, of 5.3497942, rounded off to 5.35%.

Topic 16 : ‘Syntonic Comma’ or ‘Ptolemic Comma’

The other important number we must understand before we can move on to the mathematics of 22 Shrutis, is called as ‘Syntonic Comma’ or ‘Ptolemic Comma’ because it is credited to the famous scientist Ptolemi (90-168 AD). This number is the difference in the value of Gandhar in the 3rd Saptak as found by 2 different methods.

Method 1: If we take 5 consecutive Panchams from S (100 Hz) at a distance of 50%, we come to the value of Gandhar in 3rd Saptak as 506.25 as shown below.

Method 2: However, if we double the S twice, i.e., from 100 to 200 (Upper or Tara S’), and then to 400 (Still upper S” or Ati-tara S”), and thereafter add 25% (the natural distance of G from S), we arrive at the value of Gandhar in 3rd Saptak as 400 + 25% = 500.

Thus, we got 2 values of Gandhar, 506.25 and 500.

This mathematical discrepancy by arriving at Gandhar of the 3rd Saptak by the 2 above methods should not have arisen. This natural error was demonstrated by Ptolemi and this is known as ‘Syntonic or Ptolemic Comma’. (Comma means Error as we have seen earlier).

506.25 divided by 500 = 1.0125

This measurement of 1.0125 is also fundamental in the creation of 22 Shrutis.

Topic 17 : Relationship between a Musical note and a Mathematical number

It is important for musicians to understand that any musical note can be expressed by a ‘Ratio’ using numbers. For eg.,

S (say,100 Hz) is expressed by 1/1, because, 100 X 1/1 = 100

P (150 Hz) is expressed by 3/2, because, 100 x 3/2 = 150

G (125 Hz) is expressed by 5/4, because, 100 x 5/4 = 125

S’ (200 Hz) is expressed by 2/1, because, 100 x 2/1 = 200

M (133.33 Hz) is expressed by 4/3, because, 100 x 4/3 =133.33

Such a ratio which expresses any ‘number’ has tremendous practical value as it can accurately show the ‘point’ on a string where that ‘note’ is accurately played.

For example, ‘Madhyam’ has a ratio of ‘4/3’ and it can be played at ‘3/4’ or ‘75’ % length of any string. (See Topic 33)

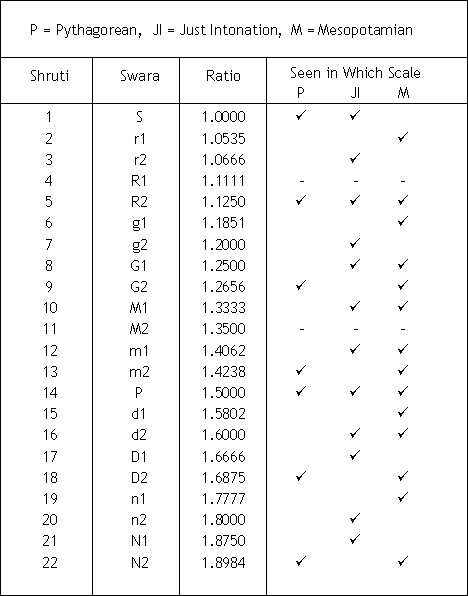

Topic 18 : Just Intonation Scale – ‘Natural’ scale in the West

There was a Natural Scale in the West as well, and was called as the ‘Just Intonation Scale’. This was named as “just” because, the scale (or Saptak) was ‘just’ (or correct) only in 1 note (or 1 Shadja). This scale was used in Medieval music in Europe from AD 550-1450. The Western music up to the 16th century employed this scale to sing, and to tune their instruments at that time, namely, the Harpsichord, and Clavichord.

With the advent (or worldwide invasion) of the ‘12-Tone-Equitempered scale’, this older but more natural scale has now become history. The same thing happened in India too. Since the availability of Harmonium and Organs from 1860s, the Indian natural scale of 22 Shrutis was forgotten and left behind due to over-dependency on ET tuned Harmoniums.

Table shows the Notes in Ancient Pythagorean scale & Just Intonation Scales

The above table shows that these 16 notes were known for centuries and we shall see later that all these are a part of 22 Indian Shrutis.

Topic 19 : The most Ancient Musical Scales in the World

Just Intonation scale is not the oldest scale in the world.

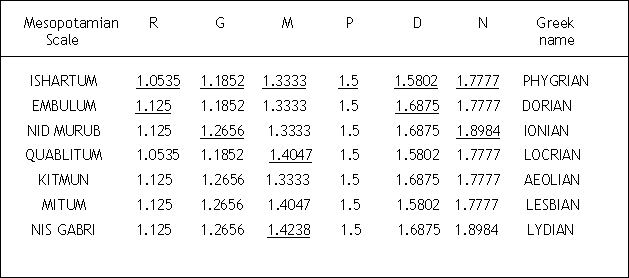

Perhaps the oldest scales on record are the ancient Mesopotamian scales (3500 BC). They were studied by Lou Harrison, as they are present on an old Babylonian cuneiform tablet in the British Museum.

Steven Nachmanvich has now made a Computer programme based on these scales as ‘The World of Music Menu’ with the help of which, we can actually play and hear these scales.

These scales were later adopted by the Greeks with their own names. (Refer to following table)

Table shows Ancient Mesopotamian and Greek Scales

These scales show that the 12 notes (underlined) in the above table with the addition of S at 1, a total of 13 notes have been known since 3500 BC and all of these also are a part of our 22 Shrutis.

Topic 20 : Efforts made by 2 prominent Indian Researchers to find our Indian scale

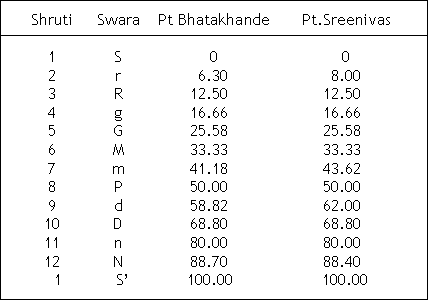

The following Table shows the differences in the positions of notes in a Saptak, as obtained by North Indian Pt. Bhatkhande and South Indian Pt. Sreenivas, when they attempted to fix the positions on the string by ‘hearing’ the notes on the string. (Refer to table in the image below).

There have been other research workers too, and their values for 22 Shrutis have been already mentioned in Topic 6.

Table shows the % differences in frequencies of Shrutis as found by ‘hearing the string’ experiments done by Hindustani Classical Music Pundit Bhatkhande and Karnatak Classical Music Pundit Sreenivas.

The lesson of this experiment was loud and clear, that the Shruti positions can never be fixed by ‘hearing’, because, at any given time, two musicians will have a different perception of Shrutis in their brain.

The possibility of such a difference will exist irrespective of the caliber of musicians.

Hence, the Shruti positions must have a ‘irrefutable mathematical base’ and that further should provide a ‘simple’ method to calculate the 22 Shrutis precisely.

Topic 21 : Discovery of 22 Shrutis from S-R-G-M

I was struggling hard to decifer the mathematics behind 22 shrutis.

As days and months passed by in tedious calculations, I was becoming certain that there had to be a ‘simpler’ method to get to the Shrutis, and I was not succeeding probably because of only trying the difficult paths.

One day, I went back to basics.

The Saptak was ‘S-R-G-M’ repeated twice, forming the complete Saptak (P-D-N-S’ are actually, S-R-G-M from P).

The secret must be here, I thought, and one day, I started studying the inter-relationships between these 4 notes.

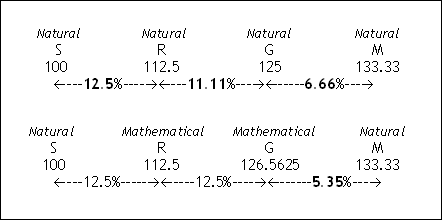

Out of these notes, S and M were “Natural” and well-defined by Nature at 100 and 133.33 % respectively. The notes R and G were different “in Nature” and “as arrived Mathematically” (By Pythagoras), giving the following differences. (Refer to following table)

Table shows Basic Mathematical percentages creating 22 Shrutis: the differences in Natural S, R, G, M ; and Natural S, M, and Mathematical R and G

My findings were as follows:

- The distances between Natural S and Natural R was 12.5%.

- The distance between Natural R and Natural G was 11.11%.

- The distance between Natural G and Natural M was 6.66%.

- The distance between Mathematical G and Natural M was 5.35%.

The figure of 5.35 struck a note in my mind, as, earlier, I had also studied the Pythagorean Octave where he had found that 5.35 was the famous Pythagorean Limma!

The notes S, R, G, and M are identified and easily sung even by small children without any musical training.

There must be a natural “setting’ in the brain to differentiate these distances, I thought. It occurred to me that surely, this must be the starting point.

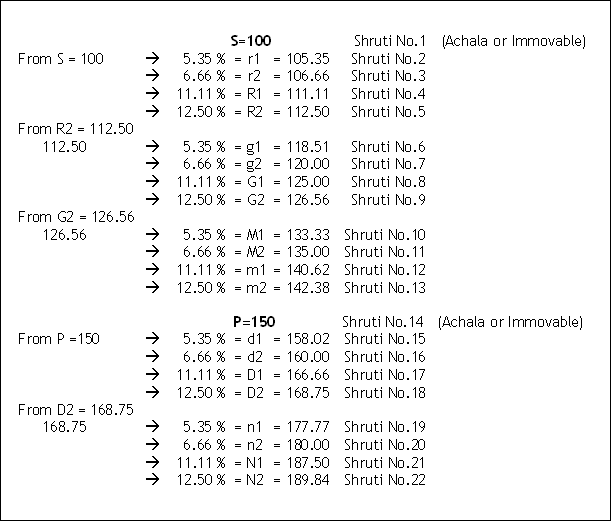

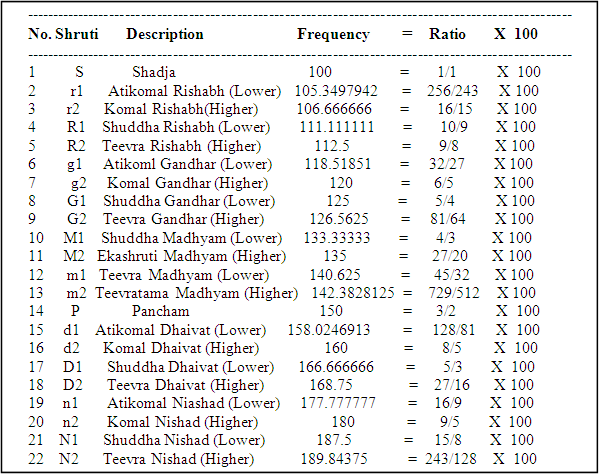

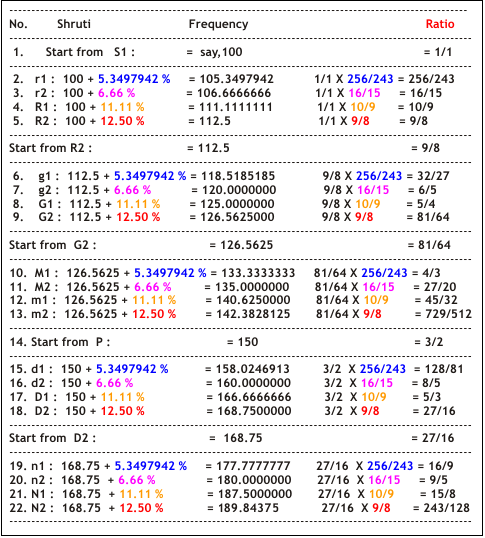

And, when I rearranged the above distances, 5.35%, 6.66%,11.11%, and 12.5%, and starting from S taken (as 100 hz), the 22 Shrutis unearthed themselves accurately to my astonishment. (Refer to following table)

Table shows S-R-G-M based Derivation of 22 Shrutis (based on % difference values between S,R,G,M, which are 5.35, 6.66, 11.11, and 12.5 respectively)

S’ of course is 200. Interestingly, the distance between m2-P; and N2-S’ was also exactly 5.35% confirming that the 22 Shrutis were fitting snugly and mathematically in the space between 100 and 200.

THE JIGSAW PUZZLE WAS SOLVED!

There were no extra pieces, and no extra space.

Topic 22 : Why “22” Shrutis Only ? : Natural Evolution

22 shrutis evolve ‘naturally’ from Shadja : Gandhar : Pancham proportions.

Actually, Shadja leads to 24 Nadas, and 22 out of them are selected as ‘Nyasa’ positions or “Shrutis”.

- Stage 1 :Production of 3 Basic/Natural shrutis - Shadja, Gandhar and Pancham

- Stage 2 : Production of 7 Basic/Natural shrutis or the Saptak - Shadja, Rishabha, Gandhar, Madhyam, Pancham, Dhaivat, and Nishad. We call these as 7 “Shuddha” swaras. And, because the 1st 6 Shrutis namely Rishabha, Gandhar, Madhyam, Pancham, Dhaivat, and Nishad take birth from Shadja, it is called as Shad (meaning 6) + Ja (meaning gives birth to) = Shadja.

- Stage 3 : Production of 24 shrutis and selection of 22 out of them.

Stage 1 : Production of 3 Basic/Natural shrutis - Shadja, Gandhar and Pancham

Let us first examine how are sounds produced in Nature. The simplest example of Natural sounds is those coming out of a single plucked string. Let us therefore take example a single string as a natural source of music. (We have already seen this in Topic 4)

Natural creation of ‘Shadja’ (Shruti No.1) : When a single string is plucked, it makes the 1st sound which we call as the “Shadja” or “Fundamental Tone”, or 1st Harmonic. For the ease of understanding, let us consider the frequency of the Shadja as 100 hz.

So, when the string is plucked, the 1st sound of 100 hz is produced. Our brain is now set after hearing this sound, to an Octave or Saptak extending from 100 hz (Shadja) to 200 hz (Tara or upper Shadja). Thus, the string vibrates in 1 full part or the whole length of the string, to begin with, to produce the “Shadja” or “Fundamental Tone”; or the 1st Harmonic with a frequency of say, 100 hz.

(Immediately thereafter, as the energy put in the string for plucking reduces, the string starts vibrating in 2 parts. This produces a sound of 200 hz called as the 2nd Harmonic. This is “Tara Shadja” as we know. As Tara Shadja is exactly double of Shadja, this is not counted as a ‘new’ shruti.)

Natural creation of ‘Pancham’ (Shruti No. 2) : Immediately thereafter, as the energy put in the string for plucking reduces further, the string starts vibrating in 3 parts. This produces a sound of 300 hz called as 3rd Harmonic. This is however perceived by our brain as of 150 hz (our brain has the spectrum of perception of 100 hz to 200 hz) or “Pancham” (the 5th) as we know

(Immediately thereafter, as the energy put in the string for plucking reduces further, the string starts vibrating in 4 parts. This produces a sound of 400 hz called as 4th Harmonic. This is perceived by our brain as of 200 hz (our brain has the spectrum of perception of 100 hz to 200 hz) or Tara Shadja again. As Tara Shadja is exactly double of Shadja, this is not counted as a ‘new’ shruti.)

Natural creation of ‘Gandhar’ (Shruti No. 3) : Immediately thereafter, as the energy put in the string for plucking reduces further, the string starts vibrating in 5 parts. This produces a sound of 500 hz called as 5th Harmonic. This is perceived by our brain as of 250 hz or 125 hz (our brain has the spectrum of perception of 100 hz to 200 hz) or Gandhar.

After this stage, the energy put in the string for plucking reduces so much that further harmonics (6th, 7th, 8th and so on) are barely heard.

This process shows that the 1st 3 (different) Natural sounds created are always Shadja, Gandhar and Pancham at a ratio of 100 : 125 : 150. Therefore these 3 are the fundamental notes or 1st 3 Natural shrutis in Indian Classical Music.

Stage 2: Production of 7 Basic/Natural shrutis or the Saptak - Shadja, Rishabha, Gandhar, Madhyam, Pancham, Dhaivat, and Nishad. We call these as 7 “Shuddha” swaras.

Natural creation of ‘Madhyam’ (Shruti No.4) : After Shadja, Gandhar and Pancham are known, the 4th note is Madhyam. We know musically that Madhyam:Tara Shadja ratio/bhava/relationship is that of Shadja:Pancham i.e. 100:150. Now,Tara Shadja is 200. Therefore, Madhyam has to be 133.333333 so that this ratio is preserved.

Natural creation of ‘Dhaivat’ (Shruti No.5) : The 5th note is Dhaivat. We know musically that Dhaivat is the ‘Gandhar’ of ‘Madhyam’, or, musically Madhyam:Dhaivat ratio/bhava/relationship has to be that of Shadja:Gandhar i.e. 100:125. Since, Madhyam is at 133.333333, Dhaivat comes at 166.666666 to preserve this ratio.

Natural creation of ‘Nishad’ (Shruti No.6): The 6th note is Nishad. We know musically that Nishad is the ‘Gandhar’ of ‘Pancham’, or, musically Pancham:Nishad ratio/bhava/relationship has to be that of Shadja:Gandhar i.e. 100:125. Since, Pancham is at 150, Nishad comes at 187.5 to preserve this ratio.

Natural creation of ‘Rishabha’ (Shruti No.7): The 7th note is Rishabha. We know musically that Pancham:Rishabha ratio/bhava/relationship is that of Shadja:Pancham i.e. 100:150. Now,Pancham is 150. Therefore, Rishabha comes at 225 so that this ratio is preserved. 225 is the Tara Rishabha, hence, Rishabha in the original scale will be at 112.5.

Thus, the 1st 7 Natural sounds are produced as above. They create 3 (perfect) triads of Shadja:Gandha:Pancham, Madhyam:Dhaivat:Tara Shadja, and Pancham:Nishad:Rishabha; which are extremely harmonic and hence individually extremely melodic.

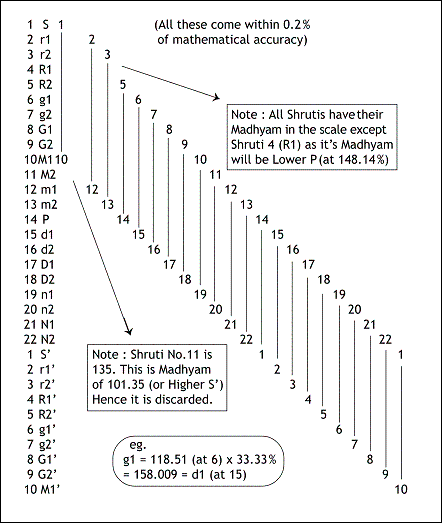

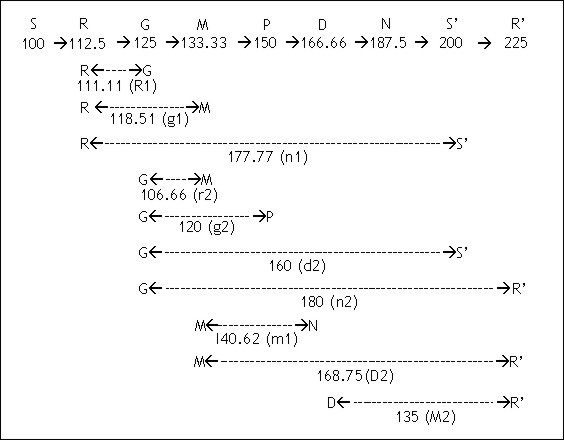

Stage 3: Production of 24 shrutis and selection of 22 out of them.

Shadja created Gandhar and Pancham (Stage 1), and ratios within them created 7 Natural shrutis (Stage 2). It is unbelievable but true that all the additional shrutis are actually the ratios within 7 Natural shrutis !

**Creation of additional ‘Rishabha’ (Shruti No.8):**Gandhar (125) / Rishabha (112.5) = 111.111111 %. This means that if Rishabha (112.5) is considered as Shadja, Gandhar (125 %) is perceived as additional Rishabha, and it comes at 111.111111.

Creation of ‘Komal Gandhar’ (Shruti No.9): Madhyam (133.333333) / Rishabha (112.5) = 118.51851851 %. This means that if Rishabha (112.5) is considered as Shadja, Madhyam (133.333333 %) is perceived as Komal Gandhar, and it comes at 118.51851851.

Creation of additional ‘Pancham’ (Shruti No.10): Dhaivat (166.666666) / Rishabha (112.5) = 148.148148148 %. This means that if Rishabha (112.5) is considered as Shadja, Dhaivat (166.666666 %) is perceived as Pancham, and it comes at 148.148148148.

Creation of ‘Komal Nishad’ (Shruti No.11): Tara Shadja (200) / Rishabha (112.5) = 177.777777 %. This means that if Rishabha (112.5) is considered as Shadja, Tara Shadja (200 %) is perceived as Komal Nishad, and it comes at 177.777777.

Creation of ‘Komal Rishabha’ (Shruti No.12): Madhyam (133.333333) / Gandhar (125) = 106.666666 %. This means that if Gandhar (125) is considered as Shadja, Madhyam (133.333333 %) is perceived as Komal Rishabha, and it comes at 106.666666.

Creation of additional ‘Komal Gandhar’ (Shruti No.13): Pancham (150) / Gandhar (125) = 120 %. This means that if Gandhar (125) is considered as Shadja, Pancham (150) is perceived as additional Komal Gandhar, and it comes at 120.

Creation of ‘Komal Dhaivat’ (Shruti No.14): Tara Shadja (200) / Gandhar (125) = 160 %. This means that if Gandhar (125) is considered as Shadja, Tara Shadja (200) is perceived as Komal Dhaivat, and it comes at 160.

Creation of additional ‘Komal Nishad’ (Shruti No.15): Tara Rishabha (225) / Gandhar (125) = 180 %. This means that if Gandhar (125) is considered as Shadja, Tara Rishabha (225) is perceived as Komal Nishad, and it comes at 180.

Creation of ‘Teevra Madhyam’ (Shruti No.16): Nishad (187.5) / Madhyam (133.333333) = 140.625 %. This means that if Madhyam (133.333333) is considered as Shadja, Nishad (187.5) is perceived as Teevra Madhyam, and it comes at 140.625.

Creation of additional ‘Dhaivat’ (Shruti No.17): Tara Rishabha (225) / Madhyam (133.333333) = 168.75 %. This means that if Madhyam (133.333333) is considered as Shadja, Tara Rishabha (225) is perceived as additional Dhaivat, and it comes at 168.75.

Creation of additional ‘Madhyam’ (Shruti No.18): Tara Rishabha (225) / Dhaivat (166.666666) = 135.

This means that if Dhaivat (166.666666) is considered as Shadja, Tara Rishabha (225) is perceived as additional Madhyam, and it comes at 135.

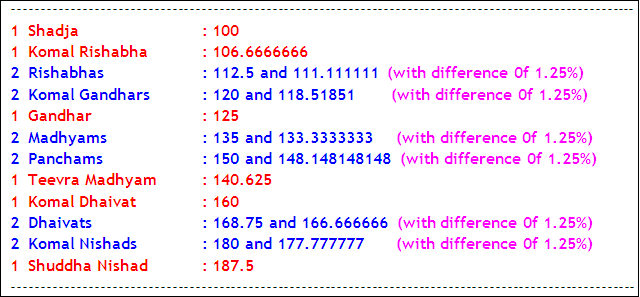

When the above 18 shrutis are arranged in a sequence, we realize that we have found:

Thus it can be seen that we have obtained from nature,

- 6 single shrutis (in red),

- 6 pairs of shrutis (in blue),

- And, the difference between each of the 6 pairs is exactly 1.25 % !!

Nature is in fact dictating that the difference between 2 shrutis (variants) for the same Swara should be 1.25 %! Hence, the missing partners of all 5 single shrutis are given by this difference of 1.25 %.

(For example, the missing partner of Komal Rishabha (106.666666) is at 105.3497942 because when 1.25 % is added to 105.3497942, we get 106.666666. Or, the missing partner of Gandhar (125) is at 126.5625 because when 1.25 % is added to 125, we get 126.5625.

Thus when all the 6 missing partners of 6 single shrutis are calculated, we get 24 shrutis as below :

Out of these 24 shrutis, 2 superfluous shrutis are discarded. They are No.2 : Shadja (Higher) at 100.125, and No.15 : Pancham (Lower) at 148.148148148; because, Shadja and Pancham have to be only at 100 and 150 respectively, and as they are ‘fixed’ (Achala) at these places in Hindustani Classical Music.

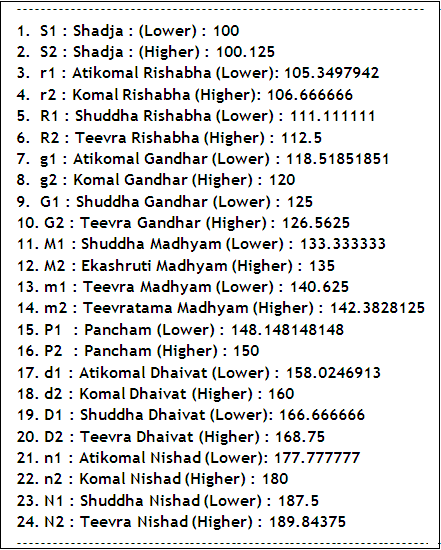

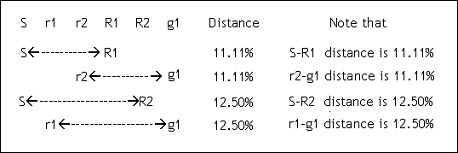

Topic 23: Why “22” Shrutis? : Natural Existence on a string

The answer is simple here.

Only 22 shrutis (places for remaining steady or nyasa) exist naturally on a single string.

As we know, there are 12 identifiable musical notes in a Saptak (Octave), namely S, r, R, g, G, M, m, P, d, D, n, and N. What is surprising is that out of these, Shadja and Pancham are playable at 1 precise point each on any string; and each of the other 10 are actually spread over a ‘region’ on the string !

For e.g. if we pluck a single string, it first makes the sound of “Shadja” or “Fundamental tone”. As we go on moving the point of playing the string from any side, it makes some unidentifiable sounds till we reach the region of r.

This is the lowermost point of perception as r by human ear (let us call it as r1). Continue ahead, and soon we reach another point which is the highermost point of perception for r by human ear (r2). In between these 2 points is the ‘region’ of r as it exists naturally on a string.

Thus, for each of the 10 notes other than the Shadja and Panchama there are lower and the higher ‘points of perception by the human ear’, creating a region on the string !

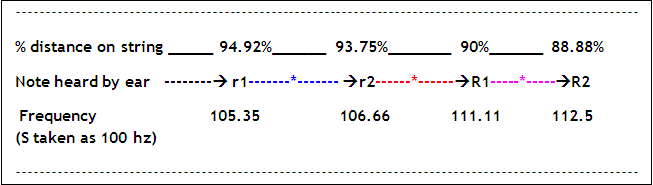

When we start playing from one end, (see figure below)

The frequency starts increasing from “Shadja”, and a point is reached where we can perceive the note as “Komal Rishabha” (See r1 : producing frequency of 105.35). We can move further and still the perception of Komal Rishabha continues.

This happens till we reach r2 (producing frequency of 106.666666). Beyond r2, the string produces a non-recognisable (besur) sound. This region can be called as ‘No man’s region’.

Thus, there are 2 limits for Komal Rishabha, r1 (lower), and r2 (higher), creating the “Swarakshetra” for Komal Rishabha.

Go further and R1 (111.111111) is played at 90 % and this is the lowermost hearing limit for the perception of “Shuddha Rishabha”. Similarly, R2 (112.5) is played at 88.88 % and this is the highermost hearing limit for the perception of “Shuddha Rishabha”.

Only if we pluck the string anywhere in between 88.88 %, and 90 %, human brain will perceive the note as “Shuddha Rishabha” (“Swarakshetra” for Shuddha Rishabha.

We find 2 such points each for 10 notes : r, R, g, G, M, m, d, D, n, and N; a total of 20 points. For Shadja and Pancham, there is only 1 point each. This makes a total of 20 + 2 = 22 shrutis.

All the frequencies ‘in-between’ the 22 shrutis (those in ‘No man’s region’) are called as “Nadas’ and they are used to ‘connect’ the shrutis for creating ‘alankars’ (e.g., aalap, meend) in an actual performance.

However, we can not ‘stay’ on them as they would sound ‘besur’ (out of tune). In other words, Nadas (in No man’s region’) are connections, and ‘Shrutis’ are stations.

The 12 positions of the 12-Tone-Equi-Tempered (12-TET) scale lie exactly ‘in-between’ the 20 points for each of the 10 notes, and thus, lie at un-natural positions.

See Topic 33 : Practical Use of Ratios : Playing all the 22 Shrutis on any String.

Finally what is amazing is that these 22 points on any string produce frequencies (shrutis) which arise only from the natural triad of Shadja:Gandhar:Pancham as explained in Topic 22. None of the other points on the string have any relation to Shadja:Gandhar:Pancham thus proving that only these 22 shrutis are natural.

Topic 24 : 22 shrutis – Rational Behind the Ratios

There are people who find it difficult to understand how complicated numbers like 729/512 (m2) or 243/128 (N2) arise at all, to represent frequencies of shrutis.

The following table will explain the same.

Let me explain how is a ‘Ratio’ created. Atikomal Rishabh has a frequency of 105.3497942. Which is the number when multiplied by 100 will give this frequency ? It is 256/243. 256 divided by 243 and multiplied by 100 gives 105.3497942. Hence, Ratio of Atikomal Rishabh is 256/243. This is how frequencies are expressed as ‘Ratios’.

We can also see the derivation of ratios another way in the following table.

It can be seen that there are simply 5 groupes of 4 shrutis each arising sequentially at a distance of 5.3497942 %, 6.66%, 11.11%, and 12.5 %, and this gives rise to the resulting frequencies and ratios of 22 shrutis.

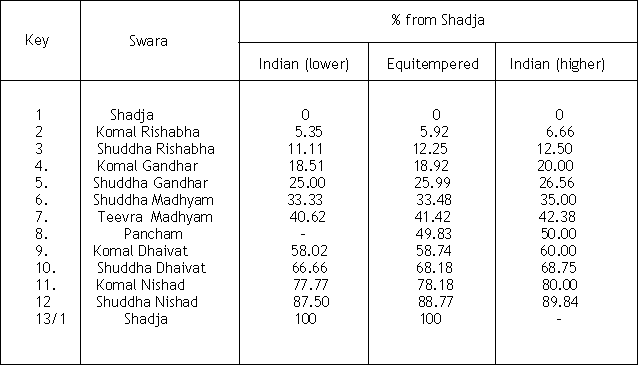

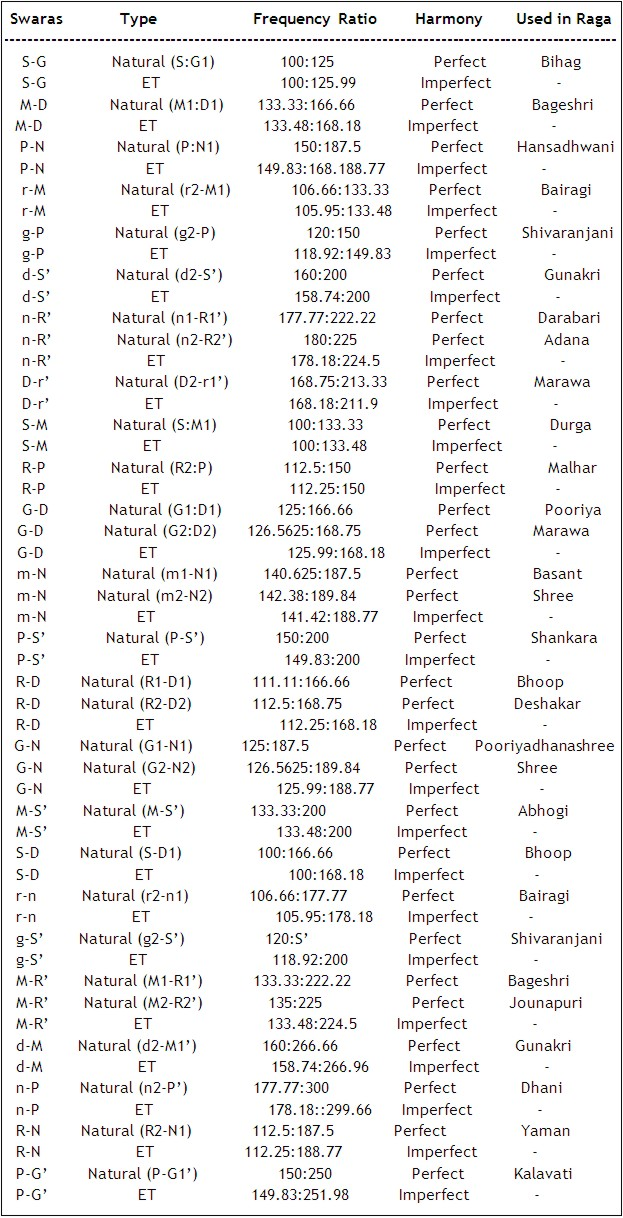

Topic 25: Difference between Equitempered notes and Indian Musical Notes

To our astonishment, it will be seen that NONE of the notes in these 2 scales are identical. Hence, if we take Equitempered Harmonium for practice or accompaniment, our voice can only get set to wrong musical notes as shown below.

Table shows the difference between Equitempered notes and Indian musical notes.

All the tempered notes come “in-between” the lower and higher shrutis, and therefore completely abolish the subtle differences or microtones of the original 22 Indian Shrutis.

Hence, singing Classical Indian music simultaneously with a Tanpura and a Equitempered harmonium can be a trying task as the frequencies of swaras will completely mismatch. Many great Indian vocalists used to dislike the Equitempered Harmonium for accompaniment.

And the reason why the Equitempered Harmonium was banned by All India Radio is also amply clear from the above table. Such microtonal accuracy may not be of so much concern in Film music, Folk music, and other non-classical versions of music; and therefore Equitempered harmonium can perhaps be tolerable only with these types of music.

Indian Classical Music however requires extreme accuracy and harmony between different notes which is preserved in the Indian Classical 22 shruti scale, and that is abolished in the Equitempered scale (ET).

Table shows the abolition of harmony between Equitempered notes and perfect harmony between Indian Natural musical notes.

Therefore, Ragasangeet of Indian Classical Music can employ perfectly harmonius pairs of shrutis which is impossible with ET scale.

Topic 26 : Shadjas and Panchams of all 22 Shrutis lie in these 22 positions only

Indian Classical music is based on S:P and S:M samvad. Therefore, all the 22 shrutis had to have their P and M within these 22 places only ! Would the Madhyams and Panchams of every Shruti found as above, ‘be’ within these 22 Shruti positions only ? Sounded unlikely, but it was so! (Refer to following tables)

The table below shows S:P Samvad of all 22 Shrutis. Interestingly, all the 22 shrutis had their respective Pancham within these 22 shruti positions only!

Now, the next table below, shows S:M Samvad of all 22 Shrutis :

Interestingly, all the 22 shrutis had their respective Madhyam within these 22 shruti positions only!

This natural arrangement allows consonant pairs of Madhyams/Panchams as shown in the previous topic to be used in Ragas.

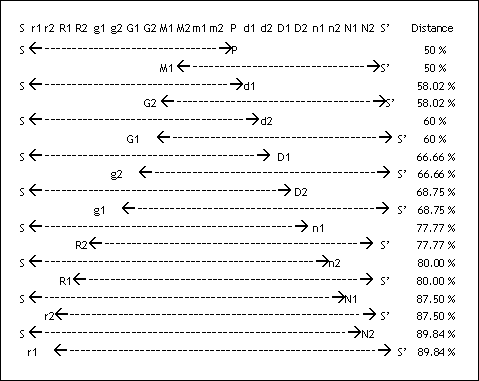

Topic 27 : Bilaterally Equiratioal positioning of 22 Shrutis

It has been argued by several research workers in the past that the distribution of 22 Shrutis is haphazard.

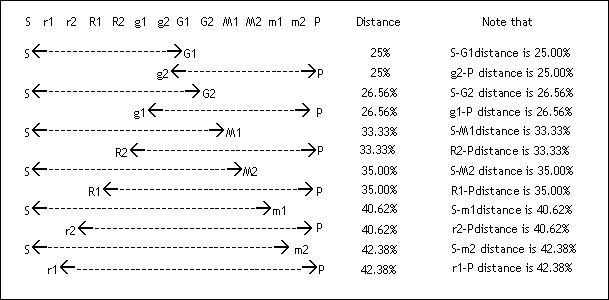

On the contrary, I discovered that the 22 Shrutis were not placed haphazardly at all, but at ‘Equiratioal’ distances from both the sides (bilaterally) in between Sa-Sa’, Sa-Pa, Sa-Ma, and Sa-Komal Ga distances. (Refer to following figures)

Figure shows Bilaterally Equi-Ratioal distribution of Shrutis between S-S’

Figure shows Bilaterally Equi-Ratioal distribution of Shrutis between S-P’

Figure shows Bilaterally Equi-Ratioal distribution of Shrutis between S-M’

Figure shows Bilaterally Equi-Ratioal distribution of Shrutis between S-g1

As the distance Sa:Ati-Komal Ga was equiratioal, this may have been the reason why our ancestors had considered Ati-Komal Ga (and not Shuddha Ga) in the ancient Saptak.

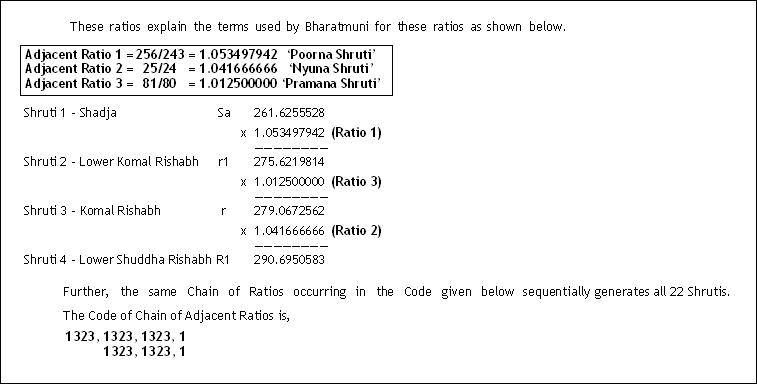

Topic 28: Serial positioning of 22 Shrutis according to accurate adjacent ratios.

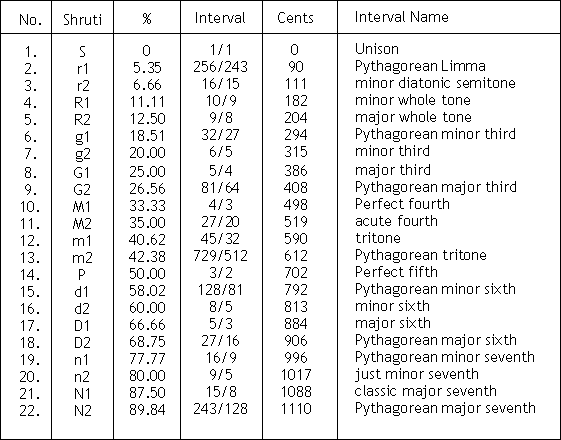

Adjacent ratio is a ratio between the frequency of the 2 successive Shrutis.

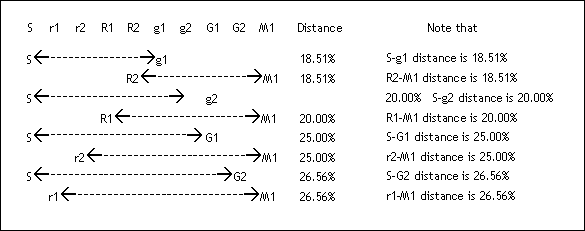

I worked out the ‘Adjacent ratios’ between all 22 shrutis and they showed a definite repetitive pattern or a unique formula, with age-old mathematical numbers governing the ratios such as the Pythagoran Limma, and Syntonic Comma.

Figure shows the definite repetitive pattern of ratios between adjacent shrutis.

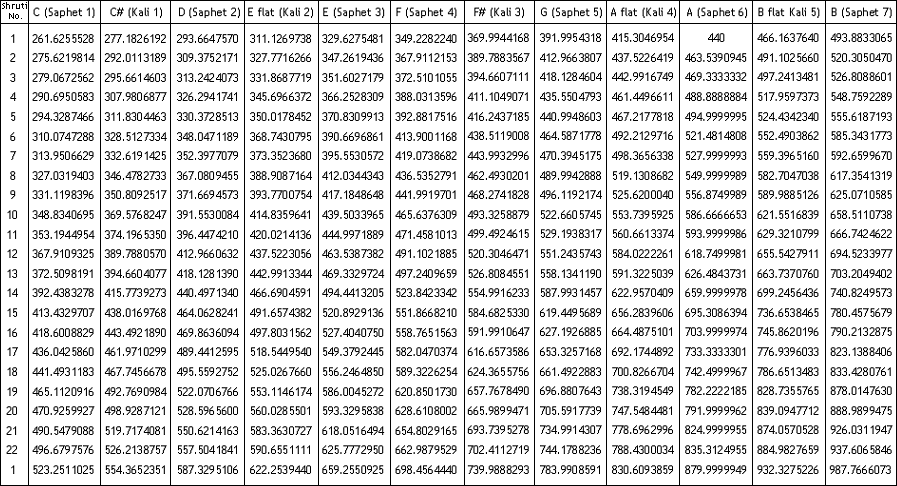

Let us take Shadja as that of the middle C in the keyboard, with the ET frequency of 261.6255528 Hz (Obtained by dividing 440 by 1.0594631, by 9 times).

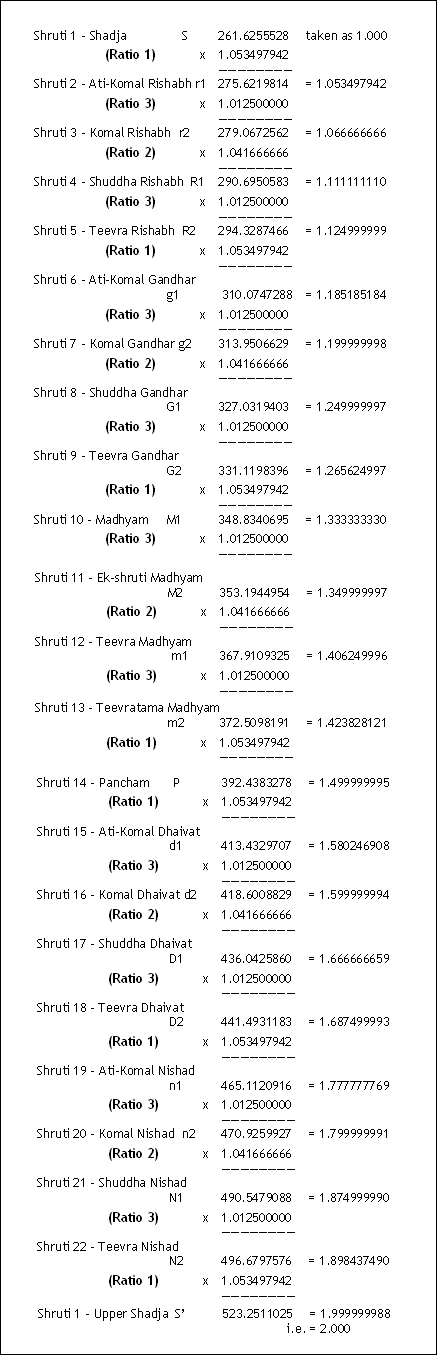

Shrutis are based on 3 Successive or Adjacent Ratios as shown below. (Refer to following tables)

Table shows 3 Principle Adjacent ratios for 22 Shrutis

Table shows the working of the Code of Adjacent ratios

Thus the cycle of the chain of adjacent ratios:

- 1,3,2,3 1,3,2,3 1,3,2,3, 1 operates between Shadja and Pancham, and

- 1,3,2,3 1,3,2,3 1 operates between Pancham and Upper Shadja.

The sequence is not haphazard, but has a peculiar design !The values of 1, 2, and 3 are those of the Adjacent Ratios 1, 2, and 3 respectively as given above.

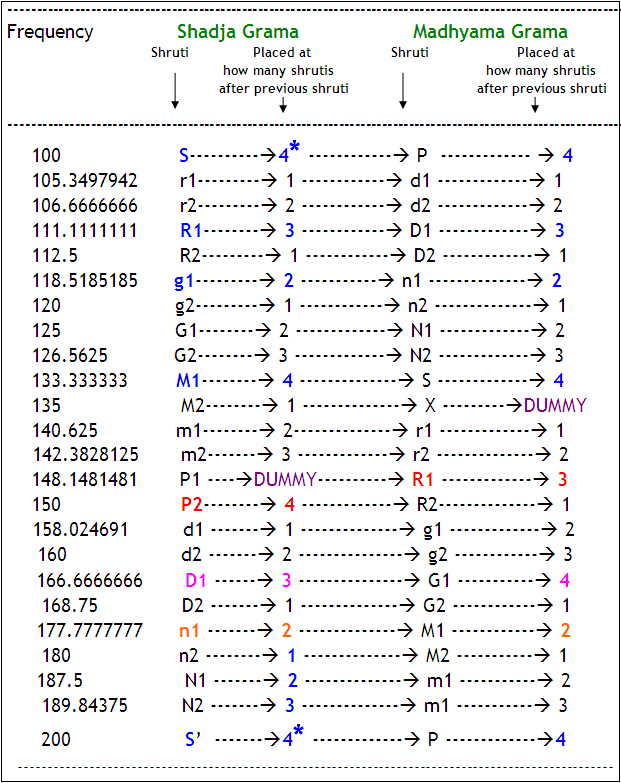

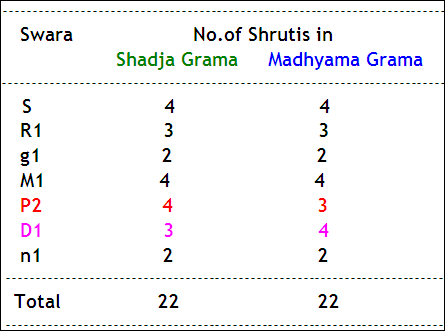

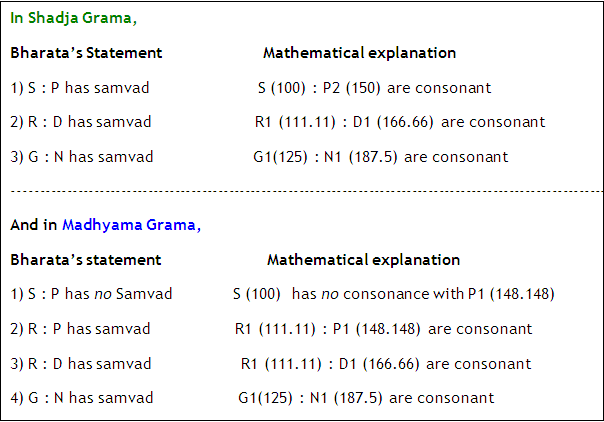

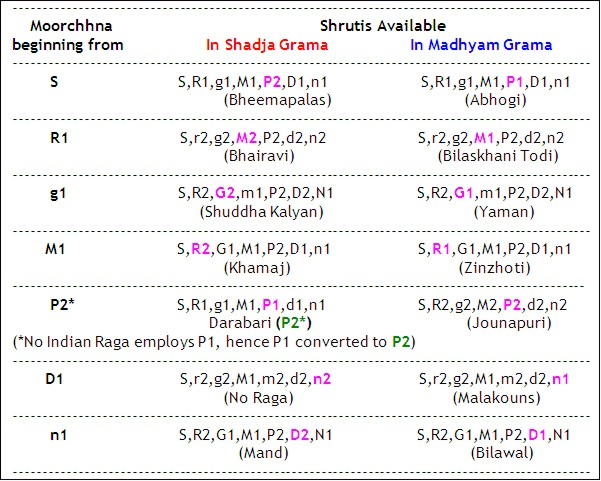

Topic 29: Bharatamuni’s Shadja and Madhyama Gramas explained

Bharata’s statements in Natyashastra (Chapter 28, Shlokas 23,24,25) about Shadja and Madhyama Gramas, the sequence of Shrutis and their mathematical explanations is provided here.

Bharatamuni stated in Natyashastra that:

“ChatushChatushChatushchaiva; Shadja, Madhyam, Pancham; DvaiDvai Nishad Gandharou; Trishri Rishabha Dhaivatashcha’”

This is translated as “there are 4 (Chatush meaning 4) Shrutis each for Shadja, Pancham and Madhyam, 2 (Dvai meaning 2) each for Nishad and Gandhar, and 3 (Trishri meaning 3) each for Rishabh and Dhaivat.

And, this is wrongly interpreted as Shadja, Madhyama and Panchama have 4 ‘variants’ (different frequencies) each, Nishad and Gandhar have 2 each, and Rishabha and Dhaivata have 3 each.

But how can this be true?

How can Shadja Madhyama and Pancham each have 4 different frequencies?

Shadja, Madhyama and Pancham have only 1 frequency each at 100, 133.3333 and 150 respectively!

The citation must therefore have another meaning.

And that true meaning is, Shadja is “placed at a distance of 4 shrutis” after it’s previous note, n1. Similarly, 3 shrutis of Rishabha (R1) means Rishabha is placed 3 shrutis after Shadja, and so on. In other words, the Shruti divisions are “Sequential” (as shown in the table below) and not “Differential”.

(Unfortunately, the above shloka (citation) is still taken literally, misinterpreted and some stalwarts wrongly believe and even sing 4 different shrutis for Shadja, Madhyama and even for Panchama today! This is a sad story.)

To understand what Bharata said, firstly, Bharata’s Shadja Grama and Madhyama Grama are explained below. Grama simply means a scale (a group of notes) starting from a particular note. e.g., Shadja Grama means scale starting from Shadja (1st note) and Madhyama Grama means scale starting from Madhyama (4th note)

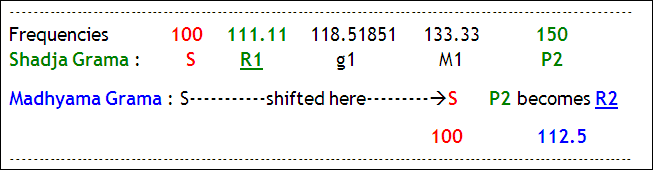

However, while shifting from Shadja to Madhyama Grama, the Rishabha (R) in Madhyama Grama (i.e., after shifting S on M1), changes as shown below.

We must remember first that at the time of Bharata, the 7 note Indian scale consisted of S, R1, g1, M1, P, D1, and n1.

It can be seen that Rishabha present as R1 in Shadja Grama automatically changes to R2 in Madhyama Grama.

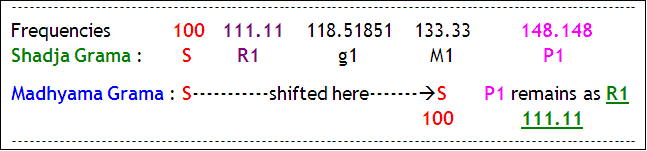

Therefore, to keep similarity of Rishabha at 111.11 also in Madhyama Grama, Bharata suggested that Panchama (of original Shadja scale i.e., P2) should be reduced by 1 shruti in Madhyama Grama .

This can be accomplished by reducing P2 from 150 to P1 = 148.148148148, which brings Rishabha at the same distance at 111.11 also in Madhyama Grama as shown below

Bharata further stated that the extent of this reduction should be termed as the “PRAMANA SHRUTI” and today we can demonstrate that, this is equal to 150/148.148148 = 1.025 !

Thus, according to Bharata, because of the change from P2 to P1, the sequence of shrutis in the 2 Gramas changes as shown below. This table is very important and unfortunately quite poorly understood by many. Please read the explanations provided below the table to get a correct understanding of what Bharata meant. It shows how a shruti from P (in Shadja Grama) is passed on to D (in Madhyama Grama).

Table showing “Sequential” positioning of Bharata’s Shrutis.

For him, Shruti was simply an expression of “Distance from previous Note”. (To reiterate, at the time of Bharata, the 7 note Indian scale consisted of S, R1, g1, M1, P, D1, and n1.)

In the above table, DUMMY means the shruti which has to be omitted in that Grama as this position is superfluous.

The above table can be understood by explanations as below which must be read patiently and carefully.

- Bharata said that Shadja or S’ is on 4th Shruti. People have unnecessarily quarelled questioning how can shrutis arise ‘before S’ if S is the 1st shruti ! We can see in the table that this S’ is on 4th shruti from n1 of the previous Saptak (Octave). This simply means that S comes 4th (or on the 4th shruti) after n1 of the lower Octave or Mandra Saptak).

- It is said that S in Shadja Grama ‘has’ 4 Shrutis and that corresponds to 4 shrutis in Madhyama Grama too. (Actually this only means that S ‘sits at’ a distance of 4 Shrutis (from n1) in Shadja Grama and also sits on the same distance of 4 shrutis in Madhyama Grama too. This does not mean that S has 4 variants (frequencies) as is wrongly believed and interpreted and even sung by some teachers !)

- Further, R1 in Shadja Grama sits on 3 Shrutis from S and that corresponds to 3 shrutis in Madhyama Grama too.

- Going ahead, g1 in Shadja Grama sits on 2 Shrutis from R1 and that corresponds to 2 shrutis in Madhyama Grama too.

- Going ahead, M1 in Shadja Grama sits on 4 Shrutis from g1 and that corresponds to 4 shrutis in Madhyama Grama too.

- The difference in 2 the Gramas starts now.

- Panchama in Shadja Grama sits on P2. This P2 in Shadja Grama sits on 4 Shrutis after M1, but since this P2 is changed to P1 in Madhyama Grama corresponding to R1, it sits on 3 shrutis (after M1) in Madhyama Grama.

- Going ahead, D1 in Shadja Grama sits on 3 Shrutis after P2 but sits on 4 shrutis in Madhyama Grama.

- Lastly, n1 in Shadja Grama sits on 2 Shrutis after D1 and sits on 2 shrutis in Madhyama Grama too.

The confusion about ‘which’ is the ‘1st’ shruti is worthless. Since to get S on 4th shruti, (as stated by Bharata), n1 will have to be the ‘1st’ shruti.

But some argue as to how n1 can arise at all in the absence of S? For them, S is taken as the starting point, N2 will be the 22nd shruti and S’ will be on the ‘23rd’ shruti.

In any case, what is important is that the distances and the frequencies of 22 shrutis in both Gramas from respective Shadjas do not change!

Thus, the no. of shrutis on which the Swaras are placed (as shown by Bharata) is as below. The difference in no. of shrutis in 2 Gramas is highlighted in colour again.

Further, some of the important statements of Bharata and their mathematical explanation is given below.

Thus, when Bharata said that S ‘has’ 4 shrutis, it only means that S sits at a distance of 4 shrutis from n1…and so on. It does not mean that S has 4 different frequencies !!

Bharata probably saw Madhyama Grama as a proper scale for singing by females, whos’ voices are approximately at a 50% higher pitch than males.

For this Female scale of Madhyama Grama, he therefore had to reduce P2 from P1 to strike a similarity of Rishabha (to reside at 111.11 as R1) in both Gramas.

Thus, Bharatamuni’s division of 22 shrutis in Shadja and Madhyam Gramas can be understood without any confusion.

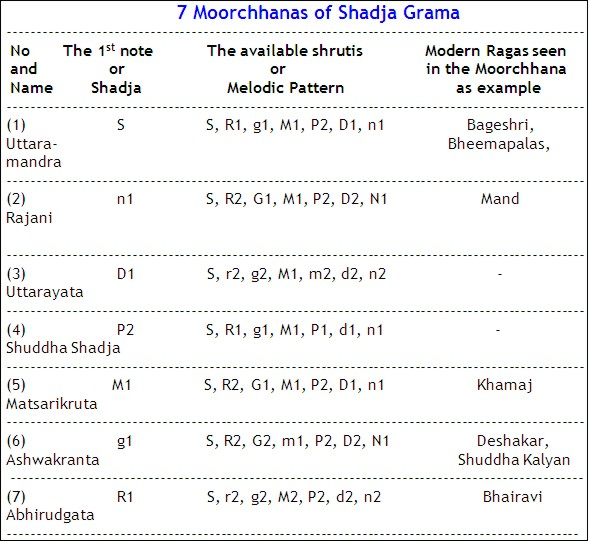

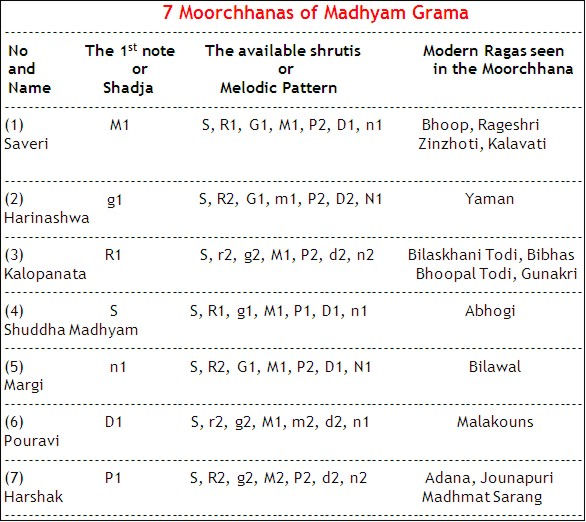

Topic 30: Bharatamuni’s Moorchhanas

After his scale was demonstrated, Bharatamuni observed that if the Shadja was serially shifted to other notes, groupes of specific notes with a melodic flavour different than the original scale became available.

There were 7 notes (S, R1, g1, M1, P2, D1, n1) in the Shadja Grama, and 7 notes (S, R1, g1, M1, P1, D1, n1) in the Madhyam Grama. Thus, Shadja could be shifted on 7 + 7 = 14 notes. He thus described 14 melodic patterns and called them “Moorchhanas”.

In Sanskrit, the word ‘Grama’ means a ‘group’ and ‘Moorchhana’ means ‘upward movement of a musical note’.

The 14 Moorchhanas thus described by Bharata are as below.

It appears that the above 14 Moorchhanas or Melodic Patterns were the original ideas and templates for creating different melodies (Ragas).

One different note (coloured in Magenta) appears in the same Moorchhana in 2 different Gramas as shown below.

It appears that Ragas available today (1000 or so) have resulted from their creators taking liberties beyond these Moorchhanas.

Nothing wrong there because Moorchhana was just a system or a way forward, not a final result.

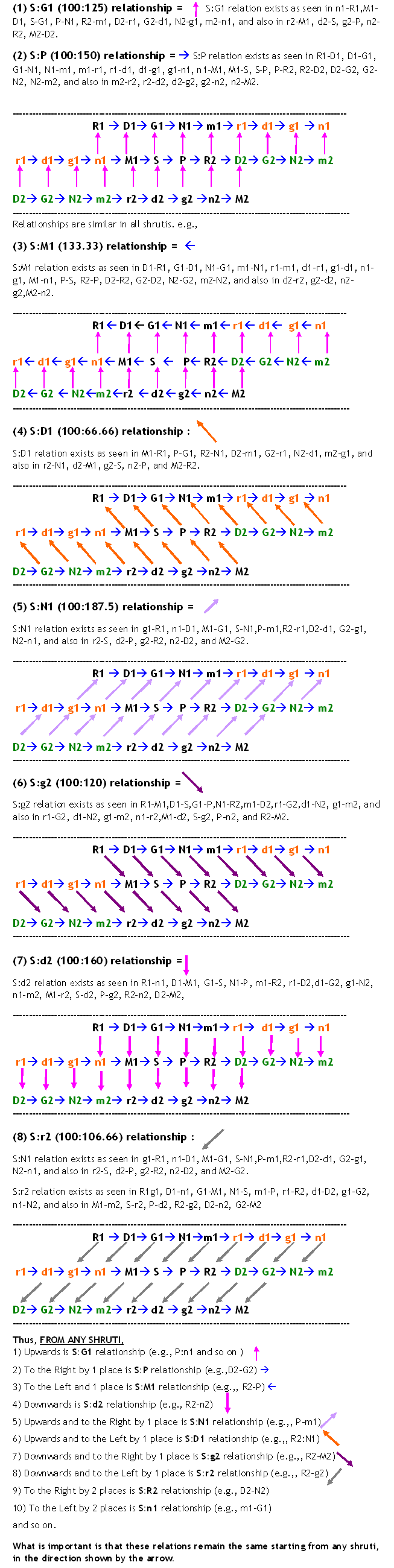

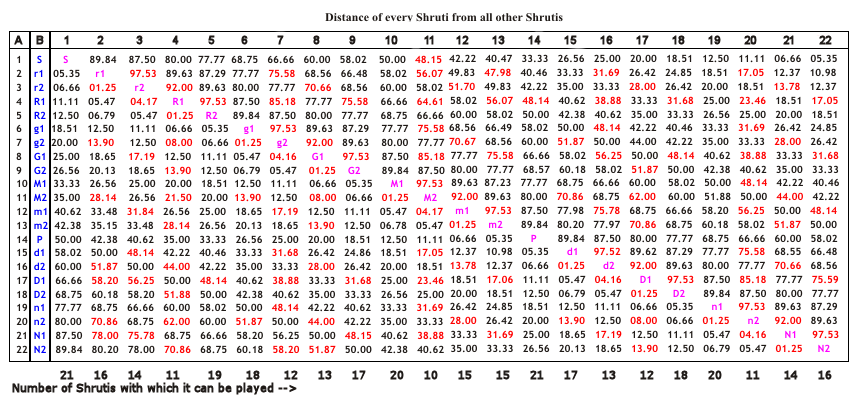

Topic 31: 22 Shruti Relationships Template

All 22 shrutis are connected to each other by various natural relationships shown by arrows of different colours and directions.

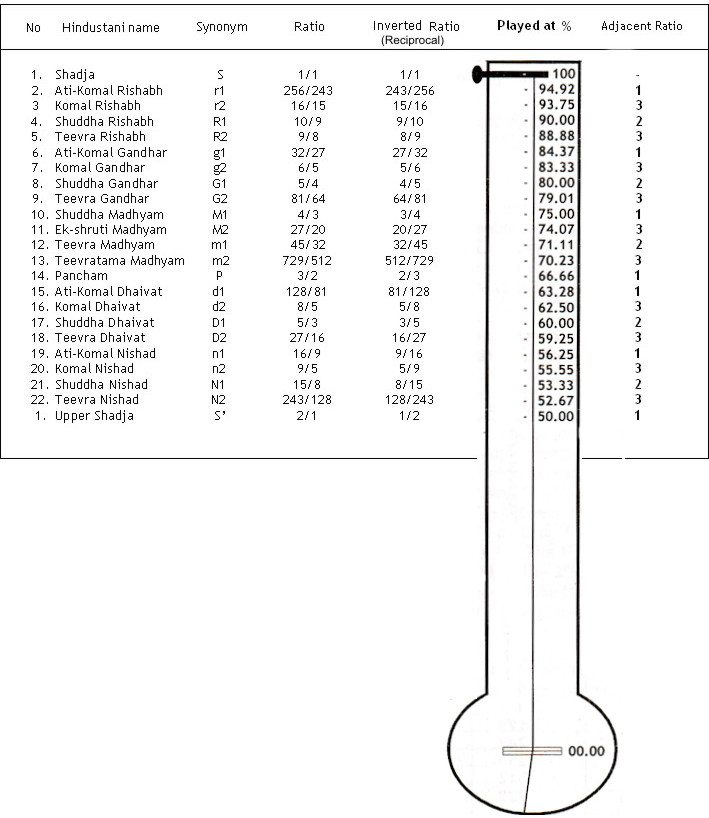

Topic 32: Practical Use of Decimals : Knowing exact distance of 22 Shrutis from Shadja

Each Shruti is expressed in ‘Decimal’. From Decimals we can calculate the % frequency distance of a Shruti from Shadja.

For eg., r1 with a decimal of 1.0535 means that it is 5.35% away from Shadja. If Shadja is at 440, r1 will be at 5.35% from 440. Now, 5.35% of 440 is 23.54.

Hence, if S is at 440, r1 will be at 440 + 23.54 = at 463.54.

Let us take another example. D1 with a Decimal of 1.6666 indicates that it is 66.66% away from Shadja, and if S is at 440, it will be 66.66% away from 440. Now, 66.66% of 440 is 293.304. Hence, if S is at 440, D1 will be at 440 + 293.304 = at 733.54, and so on.

Topic 33: Practical Use of Ratios : Playing all the 22 Shrutis on any String

Each Shruti is expressed by a ‘Ratio’. The Ratios give us the location on a string where the note is accurately playable.

All notes arising from the ratios are playable on string instruments such as a Tanpura or Sarod, or even Ek-tari. Galileo stated a law that “the frequency of vibration of a string is inversely proportional to the length of the string”.

This is simple.

For eg., R2 with a Ratio of 9/8 is played on 8/9 part of the string; or P with a Ratio of 3/2 is played exactly at 2/3 part of the string. (Refer to following table)

You can see that once we know the mathematical ratio of any Shruti, we need not play it on the string by hearing it.

It will be precisely played at the point shown in the following table. The students and beginners can very well rely on this table to adjust the Pardas of Sitar or any other string instrument. The established artists and the experts can use it as a check-point.

Table shows the % distances where all the 22 Shrutis can be accurately played on any string according to Galileo’s Law.

Adjacent Ratios mentioned in the above table are : 1 = 1.053497942, 2=1.0125, 3=1.04166

It can be appreciated that the same adjacent ratios which governed the derivation of Shrutis, also govern % distances on a string.

These % distances will operate on a string of any length, and tuned to any Shadja. On Sarod, we could show these points under the string by different colours to help the player find it absolutely accurately.

We must remember that human ear can perhaps make a mistake, but not mathematics.

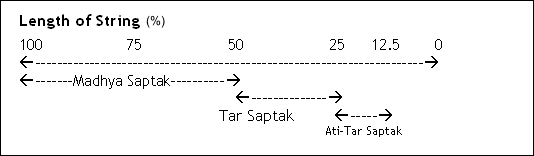

Further, you will observe that the whole Saptak (22 Shrutis) are played only in 50% of the string.

The next (Tar-Saptak) can be played exactly at 1/2 of the above distances, i.e.,from 50% to 25% length of the string. And, the next (Ati-Tar Saptak) can be played between 25% to 12.5% length of the string. Refer to the following table.

Table shows the parts of a string on which 3 Saptaks can be played.

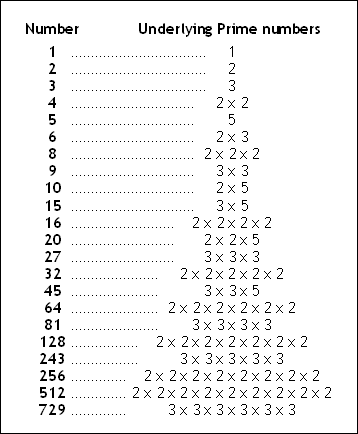

Topic 34: Relationship of ‘Numbers generating Shrutis’ and ‘Prime numbers’

It seems that Music and Mathematics are inseparable! The 22 Shrutis are expressed by Ratios with different numbers. For example, Ati-Komal Rishabha is expressed by a Ratio of 256/243, or Teevra Nishad by a Ratio of 243/128.

My analysis showed that precisely ‘22’ mathematical numbers are involved in making the Ratios for all the ‘22’ Shrutis, as shown below.

Why should only ‘22’ numbers generate ‘22’ Shrutis ? This shows that 22 Shrutis are truly a “Musico-Mathematical Marvel!” (Refer to following table)

Table shows the 22 Numbers determining the mathematical ratios of 22 Shrutis and the underlying prime numbers

It can be seen from the table that all the above 22 numbers are actually results of a combination of 4 prime numbers, 1, 2, 3, and 5.

These 22 numbers give birth to 22 Shrutis. It is also argued that the world we can perceive is made up of ‘Panch-Maha-Bhootas’ namely, Earth, Water, Fire, Air, and Space; and hence only 5 basic numbers (1, 2, 3, 5, and 4 = 2 x 2) are involved in making the 22 numbers involved in the Ratios.

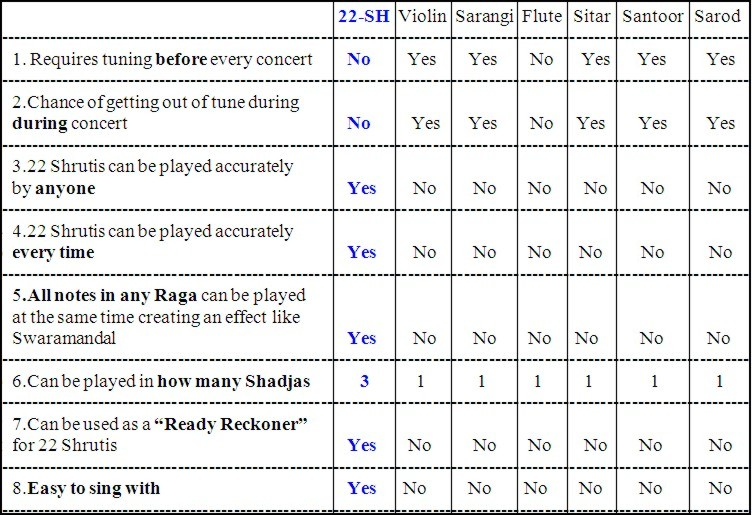

Topic 35: How to play 22 Shrutis on a Synthesizer

For tuning harmonium to 22 Shrutis, we required a stable and accurate musical note for every Shruti as a reference standard, and we had to develope a method to play all the 22 Shrutis on the Synthesizer.

The “Synthesizer” is so called because it can “synthesize and play minute frequencies” within the range of the keyboard.

This is possible because, the distance between any 2 consecutive keys can be divided into 100 equal parts or ‘Cents’ and each one of them can be played and heard very easily. Such minute adjustments in the pitch of the note are possible to be done only electronically.

For eg., if key ‘A’ is at 440 Hz, the next key ‘B flat’ will be at 440 x 1.0594631 = 466.16 Hz. The difference between 466.16 and 440, is 26.16.

When this is divided into 100 parts or ‘Cents’, 1 Cent between these 2 keys will be of 0.2616 Hz.

The 1st Cent therefore will be at 440 + 0.2616 = 440.2616 Hz. The 2nd Cent will be at 440.2616 + 0.2616 = 440.5232, and so on. Like this, all ‘100 Cents’ can be played between all keys from any Shadja to Upper Shadja.

The following table shows the ‘Cents’ (taking any key as the Shadja) on which the 22 Shrutis can be accurately played. (Refer to following table)

Table shows the ‘Cents’ on which 22 Shrutis can be played on any Synthesizer

Topic 36: Names of 22 Shrutis in Western music

Our 22 Shrutis are basically presice sounds within an Octave (Saptak). Sounds are a natural phenomena and cannot be ‘owned’ by anybody.

Hence, our Shrutis which form the foundation of Indian Classical Music, do have ‘Western’ recognition and also names as below.

The Western names come from whether the tone belonged to the Just Intonation or Pythagorean or any other known scale.

Becoming conversant with this terminology will help us to interact with Western musicians and to explain to them the positions of our 22 Shrutis. (Refer to following table)

Table shows Western Terminology of 22 Shrutis.

Topic 37: Relation of 22 Shrutis with the 7 Natural notes

The % distances of all the 22 Shrutis from Shadja are actually the % distances within the 7 Natural notes ! (Refer to following table)

For example, if we consider R at 112.5 as 100, M at 133.33 comes at 118.51.

If we consider G at 125 as 100, S’ at 200 comes at 160.

Thus, 17 Shrutis as shown above are also based only at % distances between natural Swaras.

It can be seen that 2 positions of the same swara have appeared here, namely:

- 2 Rishabhas : 111.11(R1) and 112.5(R2), and 112.5/111.11 = 1.0125

- 2 Komal Gandhars : 118.51(g1) and 120(g2), and 120/118.51 = 1.0125

- 2 Madhyams : 133.33(M1) and 135(M2), and 135/133.33 = 1.0125

- 2 Dhaivats : 166.66(D1) and 168.75(D2), and 168.75/166.66 = 1.0125

- 2 Komal Nishads : 177.77(n1) and 180(n2), and 180/177.77 = 1.0125

Very interestingly, the ratio between all these is 1.0125! This has to be therefore the ratio in all other missing Shruti-pairs (r1-r2, G1-G2, m1-m2, d1-d2 and N1-N2) also.

And in fact, it is so!

As we know now, this value of 1.0125 is the ratio of “Pramana Shruti”.

Thus, one and all the % distances of 22 Shrutis from Shadja are actually found between the 7 “Natural” Swaras. This should be a great revelation.

Topic 38: The difference between Hindustani and Carnatic Classical Music systems

In reality, the 22 shrutis are ‘same’—as the human ear is the ‘same’ all over the world, the perception of 12 universal notes (12 Swaras) changing at 22 points (22 shrutis) on any string, also remain the same. (See ‘Play the shrutis yourself’ section on Homepage)

However, the names of Swaras and Shrutis are different in the Hindustani and Carnatic systems. They are given in the following table, along with the names of Swaras in respective systems in bracket.

- Shat-sruthi Rishabham as a swara can not have Pancha-sruthi Rishabham as a sruthi ! Hence, this Swara should be called as ‘Pancha-sruthi Rishabham or Sadharana Gandharam’ only.

- This is wrongly termed as ‘Teevra Madhyam’. The dictionary meaning of Teevra is that which denotes the ‘loudness’ or ‘volume’ of sound, not frequency. Tara is the correct word, meaning ‘frequency’ of sound. This Madhyam is of a higher ‘frequency’, not of a higher ‘loudness’, and hence should be called as ‘Tara’, and not ‘Teevra’ !

- Chatu-sruthi Daivatham as a swara can not have Tri-sruthi Daivatham as a sruthi ! Hence, this Swara should be called as ‘Tri-sruthi Daivatham or Suddha Nishadam’ only.

Ratios are important to a musician – because they indicate the exact ‘position’ where the shruti can be played on ‘any’ string. e.g, 15/8 for Tara Nishad or Kakali Nishadam means that if the string was divided in 15 parts, the shruti can be played on the 8th part (8/15 = 53.33% length of the string). Similarly, 243/128 indicates that if the string was divided in 243 parts, the shruti can be played on the 128th part (128/243 = 52.67 % length of the string).

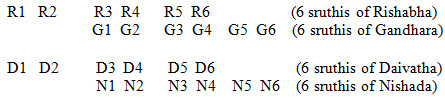

Sruthis of Gandhar and Nishad - Some experts believe that similar to Rishabha and Daivatha, there 6 sruthis of Gandhar and Nishad each, in Carnatic system. These are not different sruthis, but indicate just the ‘naming’ of sruthis. e.g., R3=G1, R4=G2, D5=N3, D6=N4 and so on, as follows.